Opera and Eye

Story Highlights

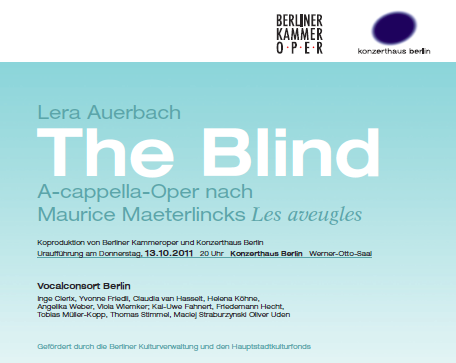

The Blind, an opera by Lera Auerbach being performed this week at the Lincoln Center Festival, has a number of unusual aspects. Unlike many opera productions today, it does not have visible titles to indicate what the singers are singing. Besides the voices of those singers, there are no other musical instruments; it is performed a cappella. It lasts only about an hour. And it has no sets or costumes. As for that last difference, the audience doesn’t notice, because they’re blindfolded (really!).

The Blind, an opera by Lera Auerbach being performed this week at the Lincoln Center Festival, has a number of unusual aspects. Unlike many opera productions today, it does not have visible titles to indicate what the singers are singing. Besides the voices of those singers, there are no other musical instruments; it is performed a cappella. It lasts only about an hour. And it has no sets or costumes. As for that last difference, the audience doesn’t notice, because they’re blindfolded (really!).

In the August 1929 issue of The Gramophone (Radio and Music) Critic, someone using the pseudonym “Tableau Vivant” (more later) wrote, “It is elementary knowledge that the appeal of opera is twofold—to the ear and to the eye.” I agree.

In the course of my research into opera’s media history, I’ve read many books the authors of which report that they fell in love with the art form on first hearing a recording or radio broadcast. Not I. I needed what could be seen onstage.

In 1673, Athanasius Kircher proposed transmitting opera’s sound without its image beyond the confines of the opera house; there’s no record that his idea was implemented. The first person actually to listen to opera sound transmitted to a home was probably Edward P. Fry in New York in 1880 (another possibility is William Hearder in Plymouth, England the same year). A contemporary account noted that, as Fry listened via telephone, he surrounded himself with photographs of the singers and read a libretto, indicating that his visual system had opera-related stimulation.

P. T. Barnum, the great American showman and sometime opera promoter (who created “Lind mania” for soprano Johanna Maria Lind, better known as “Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale”), came up with the idea of transmitting Paris Opera performances to New York via transatlantic cable for $5 per act in 1887 (about $500 for a four-act opera in today’s money). In its August issue that year, The Electrician and Electrical Engineer scoffed at the idea. They began with cost and sound-quality concerns. “Furthermore, there is the interesting fact that the performances at the Paris Opera depend largely for their success on the scenery and ballet, the singers not ranking very high. Merely to hear a work in that great house is not a great musical treat, as matters stand.”

In the September 1919 issue of Radio Amateur News, Hugo Gernsback suggested a mechanism for “Grand Opera by Wireless” that preserved the visual element. An opera would be shot on film, the film would be distributed to cinemas and to a radio studio, all the films would start at the same moment, and the singers would lip-synch to their performances into radio microphones and be heard live in each cinema. Gernsback concluded, “The writer confidently expects that this scheme will be in use thruout the country very shortly,” but there’s no indication it was ever implemented. “Tableau Vivant,” however, in that 1929 article, had another suggestion.

In the September 1919 issue of Radio Amateur News, Hugo Gernsback suggested a mechanism for “Grand Opera by Wireless” that preserved the visual element. An opera would be shot on film, the film would be distributed to cinemas and to a radio studio, all the films would start at the same moment, and the singers would lip-synch to their performances into radio microphones and be heard live in each cinema. Gernsback concluded, “The writer confidently expects that this scheme will be in use thruout the country very shortly,” but there’s no indication it was ever implemented. “Tableau Vivant,” however, in that 1929 article, had another suggestion.

Earlier this year, I attended a production of the opera Madama Butterfly in the small city (population less than 25,000) of Rolling Meadows, Illinois, not far from Chicago’s O’Hare airport. I was impressed by how the title character and her maid, Suzuki, moved in a believably Japanese manner, including those fluid kneeling and rising motions that my body won’t even try anymore. The sets and costumes were beautifully executed, and they were lit superbly. As for the voices, what can I say? Butterfly was performed by the great Renata Tebaldi, in her prime! Incidentally, she died in 2004 at age 82.

Earlier this year, I attended a production of the opera Madama Butterfly in the small city (population less than 25,000) of Rolling Meadows, Illinois, not far from Chicago’s O’Hare airport. I was impressed by how the title character and her maid, Suzuki, moved in a believably Japanese manner, including those fluid kneeling and rising motions that my body won’t even try anymore. The sets and costumes were beautifully executed, and they were lit superbly. As for the voices, what can I say? Butterfly was performed by the great Renata Tebaldi, in her prime! Incidentally, she died in 2004 at age 82.

No, I was not at a séance, nor was I watching a movie or television production, fulfilling Thomas Edison’s vision, quoted in The Century Magazine in 1894: “I believe that in coming years grand opera can be given at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York with artists and musicians long since dead.” I was watching a live production — well, visually live. The Opera in Focus team of puppeteers and technicians was creating a live performance based on recorded sound.

Let me be clear that I was not watching a puppet opera. Puppet operas were written to be performed by puppets. One of those, Il Girello (The Walker), opened in Florence in 1670, and I can’t say it was the first. Eszterháza, the palace where Joseph Haydn was composer-in-residence, had both an opera theater and a puppet-opera theater. Haydn was formally introduced to Empress Maria Theresa in 1773 when she attended the composer’s puppet opera Philemon und Baucis.

The tradition has been somewhat updated. In 2010, Gizmodo.com ran the headline, “Robot Opera Is Less Madame Butterfly, More ‘Oops I Dropped a Butterfly Screw.’” The story was about what some called “the first robot opera,” Death and the Powers by Tod Machover, who heads the Opera of the Future group at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. I like the story and what I’ve heard and seen of recordings of its performances, but calling it the “first” robot opera ignores such earlier works as Gary Xaoui’s Foibles Mench.

The tradition has been somewhat updated. In 2010, Gizmodo.com ran the headline, “Robot Opera Is Less Madame Butterfly, More ‘Oops I Dropped a Butterfly Screw.’” The story was about what some called “the first robot opera,” Death and the Powers by Tod Machover, who heads the Opera of the Future group at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. I like the story and what I’ve heard and seen of recordings of its performances, but calling it the “first” robot opera ignores such earlier works as Gary Xaoui’s Foibles Mench.

Robots and puppets seem to have three main functions in opera. One is operas written for them, from that 1670 puppet opera to this year’s Casparo, Luc Steels’s robot opera presented by Vrije Universiteit Brussel’s Artificial Intelligence Lab.

Another is as a stage effect or convenience. Productions of Siegfried, for example, often use a puppet or robot to depict the dragon; the production I attended of Xavier Montsalvatge’s El Gato Con Botas (Puss in Boots) used puppets for many of the characters; the Metropolitan Opera’s current production of Madama Butterfly has a puppet as the child.

The Opera in Focus Madama Butterfly I saw in Rolling Meadows, however, is more from a third purpose of puppets (or robots) in opera: providing a visual element for sound-only media. That’s what “Tableau Vivant” had in mind in the article, “Gramophone-Opera with a Model Stage.” The writer actually suggested that listeners to opera recordings should build their own model stages to have something to watch. That’s also what The New York Times covered in their 1938 story headlined “Marionettes Act Out Radio Opera,” in a performance for children unable to leave St. Vincent’s Hospital.

Before that marionette-assisted radio transmission of The Barber of Seville from the Metropolitan Opera, and even before the “Tableau Vivant” suggestion of model stages for listeners to recordings, however, there was Ernest Wolff, who was so moved when he attended a performance of Carmen that he built quite an elaborate puppet opera theater in his basement. Reports vary as to his age at the time and the exact moment he carved his first opera puppet, but he seems to have been 12, and it was probably in 1926 (see http://bit.ly/PuppetOpera).

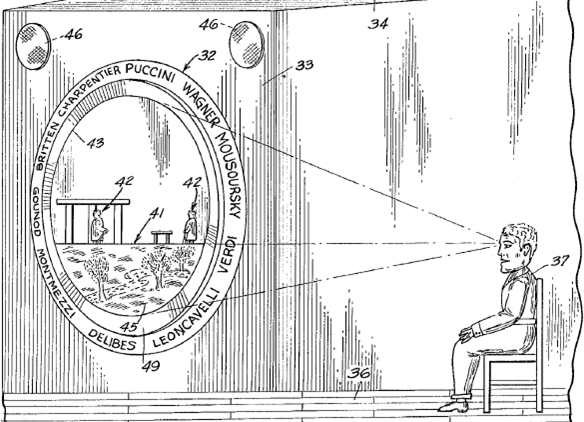

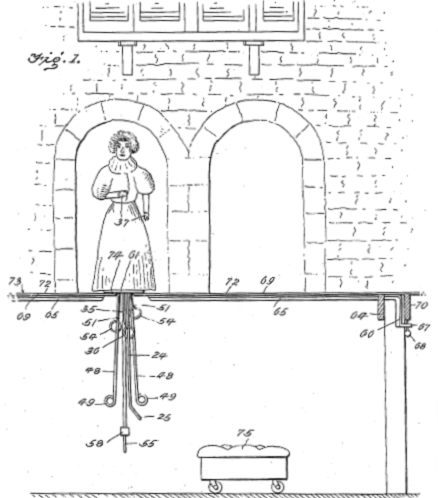

His facility grew more elaborate, and it started touring. The Gas Industries of America and RCA Victor sponsored a six-month engagement of his Miniature Opera Company at the 1939 World’s Fair, with 840 performances of six operas. He and his mother were granted U.S. patent 2,327,234 for an elaborate system of under-stage puppet control, including rolling stools for the puppeteers. Before joining the U.S. Army to serve in World War II, Wolff agreed to lend the owner of Chicago’s Kungsholm restaurant, who wanted to establish a puppet-opera theater, some puppets and scenery.

His facility grew more elaborate, and it started touring. The Gas Industries of America and RCA Victor sponsored a six-month engagement of his Miniature Opera Company at the 1939 World’s Fair, with 840 performances of six operas. He and his mother were granted U.S. patent 2,327,234 for an elaborate system of under-stage puppet control, including rolling stools for the puppeteers. Before joining the U.S. Army to serve in World War II, Wolff agreed to lend the owner of Chicago’s Kungsholm restaurant, who wanted to establish a puppet-opera theater, some puppets and scenery.

The ongoing story involves a lawsuit, a fire, another patent (3,229,411, issued to William B. Fosser, who also began doing opera puppetry in his teens), and at least two more teen-aged opera puppeteers. To cut it short, the Opera in Focus production of Madama Butterfly I saw this year has roots in the 1920s in Wolff’s basement. I recommend it highly.

Here are some links to learn more:

Popular Science, April 1940: http://blog.modernmechanix.com/boys-hobby-creates-puppet-opera/

Popular Mechanics, September 1952: http://books.google.com/books?id=jNwDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA81

Opera in Focus history section: http://operainfocus.com/history/index.html

Short video made by WTTW: http://video.wttw.com/video/1856703560