Media-Technology and Opera History

Below are most of the posts and comments that have appeared on the LinkedIn Media-Technology and Opera History group. As more are posted, they will be added here. Unless otherwise noted, all posts and comments are by me.

Below are most of the posts and comments that have appeared on the LinkedIn Media-Technology and Opera History group. As more are posted, they will be added here. Unless otherwise noted, all posts and comments are by me.

To get directly to what you want, do a browser search for a category or word of interest. The easiest way to search for the headings is to enter their number, including the period after it. In a few cases, you might be taken to a year at the end of a sentence, but a click or two more will get you where you want to go.

1. Post About Opera and Live Sound Media (2011 December 27)

2. Fandom of the Opera Lectures (2011 December 29)

3. Digital Audio, Opera, and the Met: When, How, Why, and What Was Used? (posted by Jim Lindner 2011 December 29)

4. Opera and the Oldest Photographic Motion-Picture Patent (2011 December 31)

5. Opera and the Birth of Free Matchbooks (2012 January 7)

6. How Opera Created Pay-Cable (2012 January 9)

7. Was Opera Responsible for Modern Satellites? (2012 January 11)

8. Why Opera Audiences Were Media Ready (2012 January 25)

9. How Opera Drove Videodisc Subtitling (posted by Simon Hailes 2012 February)

10. How Opera Helped Make Pelé a Sports Star (2012 February)

11. Edison, Opera, and Television (2012 March)

12. Opera and Theatrical Television (2012 March)

13. Opera and Alternative Content for Cinema — and Baseball (2012 March)

14. Opera and Lighting, Libretti, & Language (2012 April)

15. Opera, Live Television, and John Goberman (2012 April)

16. More Baseball & Opera (2012 April)

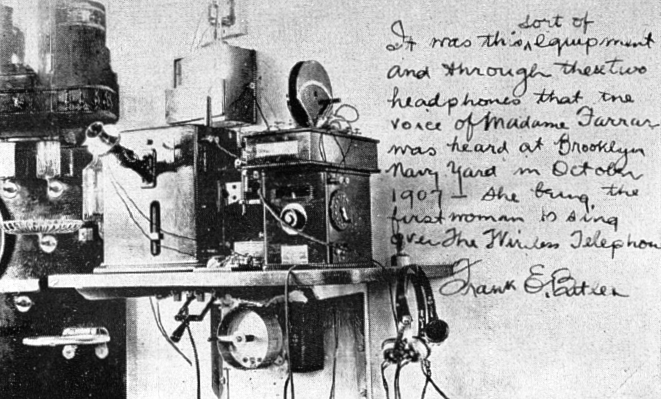

17. Opera and the First Wireless Sound Broadcast (June 2012)

18. Opera and Television – Canada Day Special (2012 July 1)

19. The Earliest Opera Recordings (2012 July)

20. More on the Baseball-Opera Hotel (2012 July)

21. Playback of Opera before the Advent of Recording (2012 July)

22. Why Is Soap Opera Called Opera? (2012 July)

23. A Little about Opera and Film Sound (2012 July)

24. Opera and the First Million-Selling Recording (2012 August 2)

25. What Was The First Opera Playback? (2012 August)

26. More on Lighting (2012 August 26)

27. Richard Tucker and the Emotion Light (2012 August 28)

28. Operas, Scores, and Movies (2012 October 9)

29. “No opera, no X-rays!” (2012 October)

30. Baseball at the Opera House and Opera in the Ball Park (2012 October)

31. The First Opera Broadcast and the 200-Ton Musical Instrument (2012 October)

32. Opera and Street Organs (2012 October)

33. Discs before Discs: the First Opera for the Masses (2012 November)

34. Opera Furniture (2012 December)

35. Opera and the Development of HDTV (2012 December)

36. The First Opera Seen Live ‘Round the World (2012 December)

37. 160 Years of Movie Technology and Opera (2012 December)

38. Opera & Media: A Very Good Year (2013 January 5)

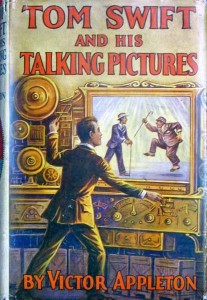

39. “The Greatest Invention,” Said Tom Swift Operatically (2013 January 13)

40. Opera & the Media: It’ll Never Fly (2013 January 20)

41. Opera and the Invention of Broadcast Rights (2013 January 24)

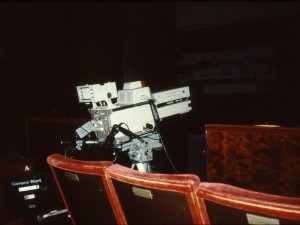

42. Opera House Video Production (posted by Winston Tharp 2013 February)

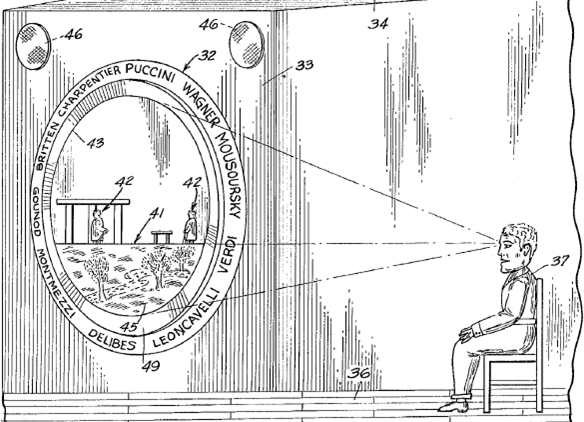

43. Opera and the Invention of Lip-Synching (2013 February 3)

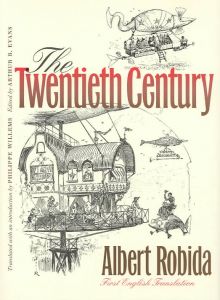

44. Super-soprano and the Ceno-orchestra! (2013 February 10)

45. Opera and Medical Media Technology (2013 February 16)

46. Opera and the Invention of Electronic Home Entertainment (2013 March 2)

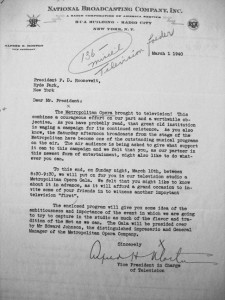

47. Opera and U.S. Commercial Television (2013 March 9)

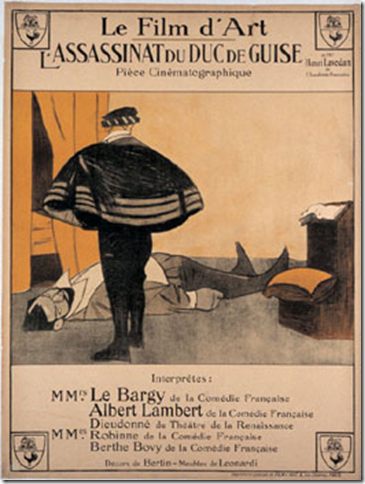

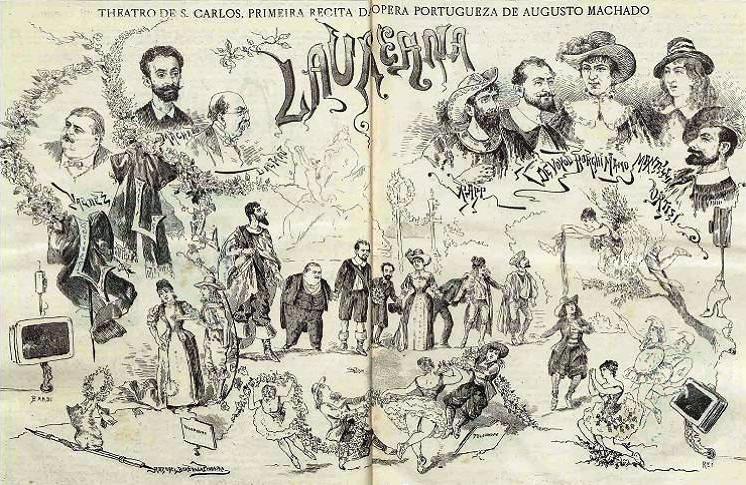

48. The First Opera Cinemacast (2013 March 21)

49. Movies at the Opera instead of Opera at the Movie theater? (posted by Pete Ludé 2013 March 22)

50. Opera and the Plazacast (2013 March 23)

51. Opera and the Advent of Color Television (2013 April 6)

52. The Eidoloscope and the Opera That Wasn’t (2013 April 13)

53. Opera and Stereoscopic 3D (2013 April 20)

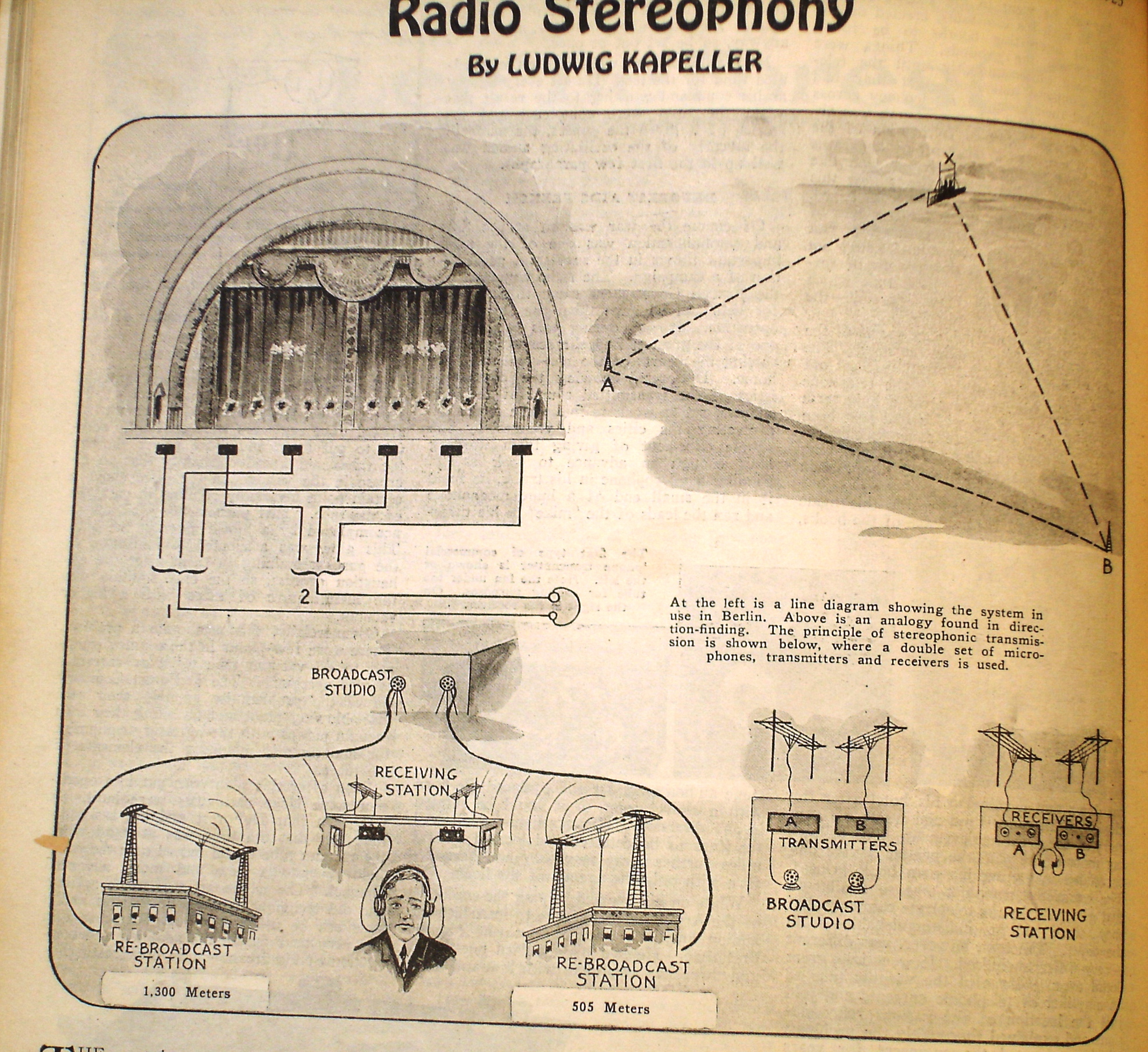

54. Opera and Stereo Sound (2013 April 27)

55. Opera and the Invention of the Newscast (2013 May 19)

56. Public Executions, Prostitution, and the First Opera House (2013 June 4)

57. Opera and the First Snapshot (2013 June 13)

58. Opera and Neutrinos (2013 June 22)

59. Unstageable Operas (2013 June 29)

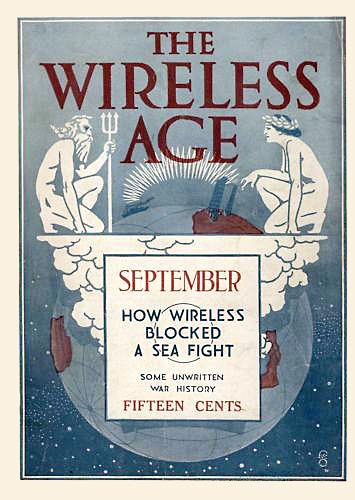

60. Opera and Eye (2013 July 10)

61. Opera and Radioactive Music (2013 July 21)

62. Opera and Outer Space (2013 August 1)

63. Opera, the Navy, and Radio (2013 August 16)

64. The Tenor, the Impresario, and the Invention of Electronic Home Entertainment (2014 March 11 – updated version of discussion 46)

65. Inside-Out (2014 April 2)

66. Opera Streamed in Beyond-HDTV Resolution (2014 May 5)

67. The First Parabolic Mic (2015 August 28)

68. Sports, Opera, and Pay-Cable (2015 October 9)

69. The First Bootleg Recording (2016 February 24)

70. Happy 54th Birthday, Rossini, Fax Pioneer (2016 February 29)

71. The Impresario Who Invented the Movie Theatre (2016 November 18)

72. The Polish Polymath Who Came Up with Opera for Television — in 1878 (2017 February 10)

73. Virtual Reality Opera (2017 June 27)

1. Post About Opera and Live Sound Media (2011 December 27)

Here is a blog post I did in January 2010 about the 100th anniversary of opera radio broadcasts. I have some more-recent info, but this is a good overview: https://staging.sportsvideo.org/blogs/?blog=schubin-cafe&news=100th-anniversary-today

2. Fandom of the Opera Lectures (2011 December 29)

I give illustrated lectures on the subject of The Fandom of the Opera: How the Audience for a Four-Century-Old Art Form Helped Create the Modern Media World. You can find many of them in the download section of SchubinCafe.com: https://staging.sportsvideo.org/blogs/?blog=download

Some are also available on YouTube. Search for schubin opera.

3. Digital Audio, Opera, and the Met: When, How, Why, and What Was Used? (posted by Jim Lindner 2011 December 29)

While working on a Met audio archive remastering project some years ago, I came upon some very early digital audio recordings that used the U-matic format to record on: the somewhat infamous PCM-1600. I had worked with them occasionally many years ago when they were being used but never saw them in routine use, nor did I ever see that many PCM-1600 recordings in any other vault of any other archive. I was particularly surprised to find them in the collection of the Met, as these devices were pretty unusual to find and were almost always in studios and more for experimentation then real day to day work. Clearly someone was experimenting and taking some risks. Was that you Mark? I would be interested to learn about the first experimentation with digital audio at the Met and other opera houses and how the PCM-1600 came to be used at the Met on such a routine basis.

Mark Schubin: Digital audio and opera actually goes back a little farther, to 1976. Two things happened that year, both related to one of only two people to have won an Academy Award, an Emmy, and a Grammy as well as awards from the Audio Engineering Society, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, and the Society of Motion-Picture and Television Engineers: Tom Stockham (the other winner of all of those awards is Ray Dolby, who sits on the board of San Francisco Opera).

Stockham’s opera connection actually began in a non-audio area. I met him at an exhibition I put together at the Library of the Performing Arts in 1975. It was called “The Performing Arts and the Future of Television.” One of the exhibits related to the huge contrast range encountered on an opera stage, from a star in white sequins illuminated by a spotlight to a villain in black velour hidden in the shadows. Stockham suggested a way to compress the contrast using an electronic technique similar to photographic unsharp masking, and we actually built a contrast compressor that would work that way.

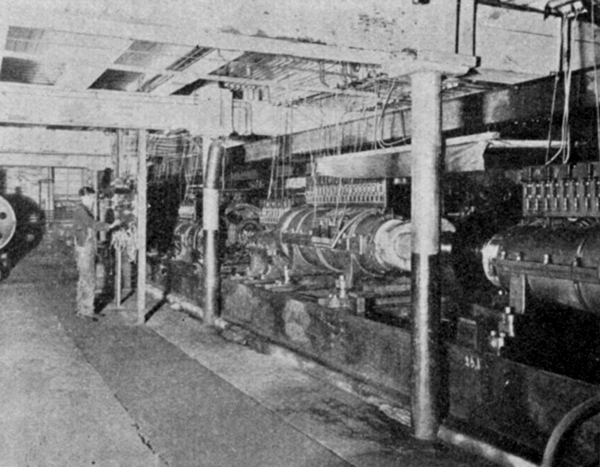

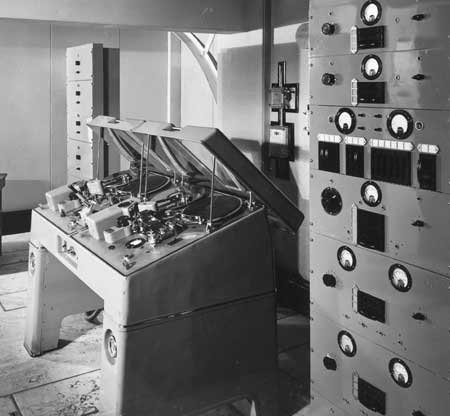

Back in sound, Stockham developed the first commercial digital-audio recording system, Soundstream, based around a one-inch-tape instrumentation recorder and a rack of equipment. He made the first commercial digital-audio recording, Santa Fe Opera’s 1976 production of “The Mother of Us All.” He also made Soundstream recordings at the Met, but I can’t remember when, so I’m not sure if they were before Santa Fe or after (they weren’t released in any case).

Back in sound, Stockham developed the first commercial digital-audio recording system, Soundstream, based around a one-inch-tape instrumentation recorder and a rack of equipment. He made the first commercial digital-audio recording, Santa Fe Opera’s 1976 production of “The Mother of Us All.” He also made Soundstream recordings at the Met, but I can’t remember when, so I’m not sure if they were before Santa Fe or after (they weren’t released in any case).

As for the PCM-1600, that was the recording system used for the first CDs. We started using it at Live from Lincoln Center in a Sony demonstration and then continued using it at the Met. I think the Met has, at one time or another, used just about every audio recording format that ever existed, from Edison cylinders to current multitrack digital recordings on different tapeless systems (so that, if a bug is discovered in one company’s software, the other recordings remain safe).

Another comment: Oops! I forgot to mention Stockham’s other 1976 digital-audio opera achievement.

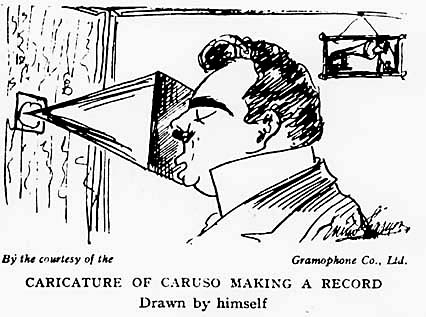

The famous tenor Enrico Caruso made many recordings. He was, in fact, hired to sing at the Met on the basis of one of his recordings (the Met’s general manager heard it). It is likely that one version of his recording of the aria “Vesti la giubba” from Pagliacci was the earliest recording to sell a million copies (it has never been unavailable since it was recorded), though the first millionth-copy sale might have been a country song by Vernon Dalhart (who was an opera singer before he became a country singer).

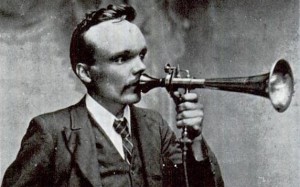

Caruso’s recordings were made in the “acoustic” recording era, when sound waves from the singer’s voice were recorded directly, with no microphones involved. To do that, the singer sang into a funnel (called a horn). Caruso even drew a picture of himself doing that.

Caruso’s recordings were made in the “acoustic” recording era, when sound waves from the singer’s voice were recorded directly, with no microphones involved. To do that, the singer sang into a funnel (called a horn). Caruso even drew a picture of himself doing that.

Stockham wanted to know what Caruso really sounded like, without the distortion introduced by the horn. So he mathematically processed the sound through a technique called blind deconvolution to restore the actual sound of Caruso’s voice. And, in 1976, he released the album Caruso: A Legendary Performer, with digitally processed acoustically recorded opera arias.

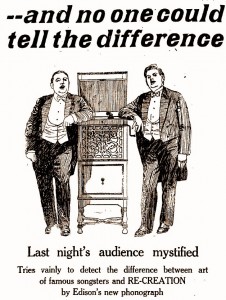

One final note: When Thomas Edison switched from cylinder to disc, he decided to use opera to promote his system in a series of “Tone Tests.” In small locations, listeners would be blindfolded and asked whether they were hearing a live singer or a recording. In large locations (such as Carnegie Hall), an opera singer might start singing, then the lights would go out, and, when the lights came back up, only Edison’s Diamond Disc Phonograph would still be on stage.

One final note: When Thomas Edison switched from cylinder to disc, he decided to use opera to promote his system in a series of “Tone Tests.” In small locations, listeners would be blindfolded and asked whether they were hearing a live singer or a recording. In large locations (such as Carnegie Hall), an opera singer might start singing, then the lights would go out, and, when the lights came back up, only Edison’s Diamond Disc Phonograph would still be on stage.

Amazingly to us, even in the acoustic-recording era, audiences said they couldn’t tell the difference! But the most-popular Tone Test singer, opera soprano Anna Case, confessed much later that she had trained herself to sound like a phonograph recording of herself.

You’ll find more about Stockham’s work (including a photo of the Soundstream recorder and Caruso’s drawing) here: https://staging.sportsvideo.org/blogs/?blog=schubin-cafe&news=the-blind-leading

4. Opera and the Oldest Photographic Motion-Picture Patent (2011 December 31)

I just posted something on SchubinCafe.com about how old stereoscopic 3D display systems are. The end of the post is about Jules Duboscq, head of special effects at the Paris Opera in the middle of the 19th century: https://staging.sportsvideo.org/blogs/?blog=schubin-cafe&news=3d-the-next-big-thing

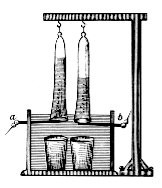

He got to be head of special effects there by creating an electric-light sunrise effect for the opera Le prophete in 1849, 30 years before Thomas Edison’s light-bulb demo. Duboscq used an electric arc, which is interesting enough, but he needed to power it, and there was no power company, so he built a power room in the opera house using Bunsen-cell batteries, which emit toxic fumes. So Duboscq developed a fume-precipitation system, later praised in Nature magazine. He later created special effects on the opera stage with an electric-light rainbow, and an electric-light fountain.

He got to be head of special effects there by creating an electric-light sunrise effect for the opera Le prophete in 1849, 30 years before Thomas Edison’s light-bulb demo. Duboscq used an electric arc, which is interesting enough, but he needed to power it, and there was no power company, so he built a power room in the opera house using Bunsen-cell batteries, which emit toxic fumes. So Duboscq developed a fume-precipitation system, later praised in Nature magazine. He later created special effects on the opera stage with an electric-light rainbow, and an electric-light fountain.

Meanwhile, he also patented a 3D viewer (a stereoscope) in 1852 and, in an addendum to the patent the same year, showed how it could be used with photographic motion pictures (a quarter century before even Muybridge). It is certainly the first 3D movie patent, but it also appears to be the first patent for photographic motion pictures of any kind.

Meanwhile, he also patented a 3D viewer (a stereoscope) in 1852 and, in an addendum to the patent the same year, showed how it could be used with photographic motion pictures (a quarter century before even Muybridge). It is certainly the first 3D movie patent, but it also appears to be the first patent for photographic motion pictures of any kind.

There’s an image of one of his surviving 3D movie discs (perhaps the only surviving one) in the post. Happy New Year!

Comments:

Jim Lindner: Your posting started me thinking pre-photography again (and maybe documented although pre-patent as well). Perhaps the impetus was not your article but because I saw “Hugo” a few weeks ago, but, either way, your comment about Duboscq started me thinking about projection that “appeared” to the audience to be 3D or real. So with that wider aperture one can take a much further view back, which at the moment has me going back past the stereopticon to the magic lantern which most certainly would “count” as being theatrical presentation and with the ability to show multiple images simultaneously, as shown in this lovely picture from the Magic Lantern Society: http://www.magiclantern.org.uk/

Jim Lindner: Your posting started me thinking pre-photography again (and maybe documented although pre-patent as well). Perhaps the impetus was not your article but because I saw “Hugo” a few weeks ago, but, either way, your comment about Duboscq started me thinking about projection that “appeared” to the audience to be 3D or real. So with that wider aperture one can take a much further view back, which at the moment has me going back past the stereopticon to the magic lantern which most certainly would “count” as being theatrical presentation and with the ability to show multiple images simultaneously, as shown in this lovely picture from the Magic Lantern Society: http://www.magiclantern.org.uk/

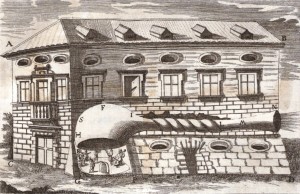

Most certainly, as you can see, these projectors are designed to all focus on the same screen area and almost certainly just the smallest offset as to provide a device that certainly was technically capable of stereoscopic display, even if by accident. So one then starts going back (visual of calendar pages flipping) way back past the Phantasmagoria (which certainly would meet this broader criterion) past Walgensten (who was in the public ghost summoning business), and there certainly were others doing it at that time to the 1650’s or so – where I am currently learning about Kircher who shows an illustration of a lensless projector which would seem to be capable of producing 3D apparitions for an audience in a very very dark room. I am trying to get a copy or reprint of his book to see it for myself, although this picture from the Princeton Library is pretty convincing: http://library.princeton.edu/libraries/cotsen/exhibitions/MagicLantern/Images/Regular/ML4.jpg

The Magic Lantern Society goes (I think) a bit too far with Giovanni de Fontana as the inventor of the Magic Lantern for our slightly tighter definition: that being a device that is both documented and capable of convincing audiences at that time of the 3D reality of the image cast ….. his is, at best, poorly defined and it would be hard to believe that the apparition cast would be believable as “real”. So I think that audiences have been thrilled with “real” 3D images for a very, very, long time.

Mark Schubin: Thanks, Jim!

I’ll probably do another post some day on the use of projection in opera. It is well documented back to 1726 in Hamburg using magic lanterns with moving-image slides (in one 1727 Hamburg production, there were motion fireworks). I cannot (yet) confirm the motion apparatus used there then, but it was common in the 19th century to have elaborate geared slides that could depict flowing fountains and the like.

I’ll probably do another post some day on the use of projection in opera. It is well documented back to 1726 in Hamburg using magic lanterns with moving-image slides (in one 1727 Hamburg production, there were motion fireworks). I cannot (yet) confirm the motion apparatus used there then, but it was common in the 19th century to have elaborate geared slides that could depict flowing fountains and the like.

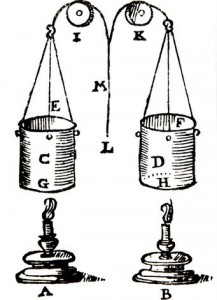

The projector used in Hamburg in 1726 was made by Pieter van Musschenbroek in Leiden in 1720. It can be seen (along with several motion-image slides) at the Boerhaave Museum in Leiden (it’s an easy trip from the Rai conference center where the International Broadcasting Convention takes place).

The “lensless” projector in Kircher’s book is generally considered to be either an error on his part or an intentional misdirection.

By the way, in 1986, The Magic Lantern Society published a magnificent book by Franz Paul Liesegang, Dates and Sources (translated and edited by Hermann Hecht) with not only magic-lantern history (“stereopticon” is a synonymous term; “stereoscope” is the term for a 3D viewer) but also cinematography’s history.

More recently (as in this opera season), digital projection has been used extensively in opera. At the Met, the Ring cycle, Damnation of Faust, Faust, Dr. Atomic, and the new Enchanted Island all rely heavily on digital projection.

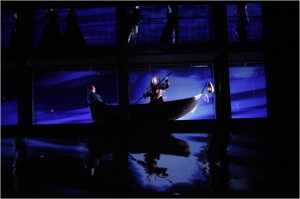

In Damnation of Faust, there’s a scene in which a gondola is being poled across the stage, the vessel and its occupants reflected in the rippling water — except there’s no water. Cameras pick up the action on the stage and feed it into computer-graphics engines, which, in turn, feed warp engines to adjust for the projection surfaces, which feed multiple overlapped projectors.

In Damnation of Faust, there’s a scene in which a gondola is being poled across the stage, the vessel and its occupants reflected in the rippling water — except there’s no water. Cameras pick up the action on the stage and feed it into computer-graphics engines, which, in turn, feed warp engines to adjust for the projection surfaces, which feed multiple overlapped projectors.

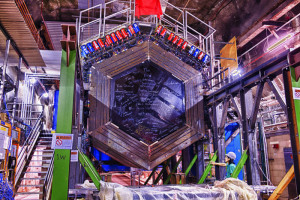

In Das Rheingold, the projection surface is “The Machine,” a sort of rotisserie spit carrying 24 long planks, each of which can rotate around the x-axis. Six projectors project from the front and three from the top, and, no matter what The Machine or any of the planks does, the projection looks painted on. The interactivity, in this case, not only allows gravel to fall down the riverbed as the Rhinemaidens swish their mermaid tails but also puts the greatest “flow of bubbles” above the mouth of the one singing loudest.

Siegfried does all that and adds depth planes appropriate to wherever any portion of any plank happens to be. Early in the opera, there appears to be a gigantic rotating root structure that audience members can see through. The whole thing is “just” selective depth-plane projections on the rotating planks. People from the computer-graphics realm all over the world have been calling the Met daily asking, “What did you do today?” And it’s all live on stage, following a different opera being rehearsed that morning and afternoon.

You can hear me discuss some of the old and new in this NPR interview: http://www.npr.org/2011/11/06/142018443/how-opera-helped-create-the-modern-media-world

5. Opera and the Birth of Free Matchbooks (2012 January 7)

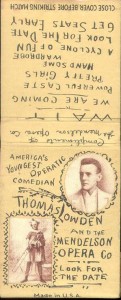

Tomorrow’s New York Times Magazine has a story about matchbooks, including how the Mendelson [sic] Opera Company created the first matchbook advertising (hand written, but with tiny photos attached). That story puts the date at 1889, though some phillumenists put the date at 1895 or 1896. The opera company gave out the matchbooks promotionally (100 or 200 of them, depending on research source).

Tomorrow’s New York Times Magazine has a story about matchbooks, including how the Mendelson [sic] Opera Company created the first matchbook advertising (hand written, but with tiny photos attached). That story puts the date at 1889, though some phillumenists put the date at 1895 or 1896. The opera company gave out the matchbooks promotionally (100 or 200 of them, depending on research source).

According to the story, a salesperson for the matchbook company thought it was a good idea and pitched it to the Pabst Brewing company, which ordered 10 million. Duke Tobacco took 30 million, and Wrigley Gum a billion. The advertising paid for the matchbooks, so they were given away free.

The Times story is here: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/08/magazine/who-made-that-matchbook.html

This link has a photo of what’s supposed to be the original: http://matchpro.org/Matchbookhistory.html

Comment: I’ve done a bit more research. Page 18 of the December 8, 1894 issue of The New York Dramatic Mirror seems to indicate that Thomas Lowden had already left what was really known as the Mendelssohn Opera Company (the matchbook shown in the link above was misspelled). That suggests that the 1889 date is correct.

Joshua Pusey filed his patent for the matchbook in 1889, so it’s conceivable the promotion was that year. It couldn’t have been too much later, as Lowden died in 1898.

Another comment: The plot thickens!

I’m happy to correct The New York Times when they make a mistake in an area in which I have some expertise, such as the development of headphones (the first consumer versions appear to have been created for opera; you’ll find more here: https://staging.sportsvideo.org/blogs/?blog=schubin-cafe&news=headphones-history-hysteria).

I am definitely not an expert on matchbooks. But the clean, recent-looking printing of the “CLOSE COVER BEFORE STRIKING MATCH” on the opera-promoting matchbook cover bothered me, so I’ve been looking around some more, and I came across this: http://www.docstoc.com/docs/17059430/Diamond-Match-Company-Manumarks-_Diamond-Quality_

I am definitely not an expert on matchbooks. But the clean, recent-looking printing of the “CLOSE COVER BEFORE STRIKING MATCH” on the opera-promoting matchbook cover bothered me, so I’ve been looking around some more, and I came across this: http://www.docstoc.com/docs/17059430/Diamond-Match-Company-Manumarks-_Diamond-Quality_

Note that it begins with a disclaimer about disagreements, so this might not be definitive, but, according to this piece, “CLOSE COVER BEFORE STRIKING MATCH” did not appear on Diamond Matchbooks until 1912.

Hmm.

Another comment: This site suggests that neither the “CLOSE COVER BEFORE STRIKING MATCH” nor the Diamond Match attribution is correct. There’s a different matchbook (right). That means the opera matchbook could be older, but the author of the linked post doesn’t think it was the first: http://www.titanicitems.com/matchbooks.htm

6. How Opera Created Pay-Cable (2012 January 9)

Here is another SchubinCafe post, this one on the 125th anniversary of pay cable: https://staging.sportsvideo.org/blogs/?blog=schubin-cafe&news=125th-anniversary-of-pay-cable

7. Was Opera Responsible for Modern Satellites? (2012 January 11)

7. Was Opera Responsible for Modern Satellites? (2012 January 11)

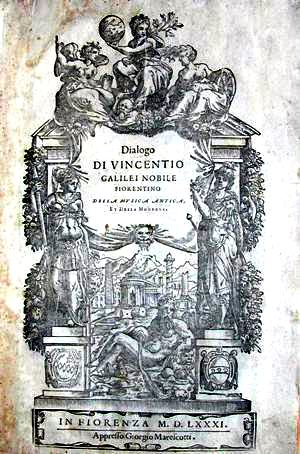

This one’s quite a stretch, but the origin of the geostationary satellite orbit (used by almost all satellites that carry television signals) can be traced back to a book (left) published in 1581. And, according to many scholars, the same book laid out the principles of opera.

If you’re interested, try the link. You will learn why Galileo is called Galileo: https://staging.sportsvideo.org/blogs/?blog=schubin-cafe&news=satellites-are-really-old

8. Why Opera Audiences Were Media Ready (2012 January 25)

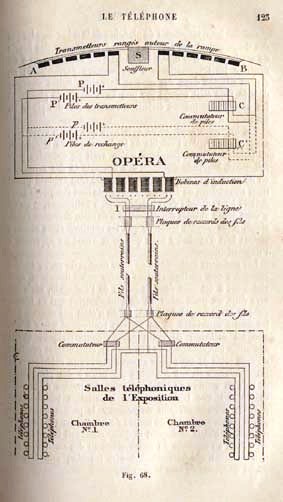

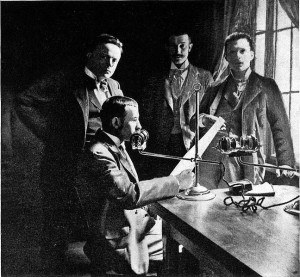

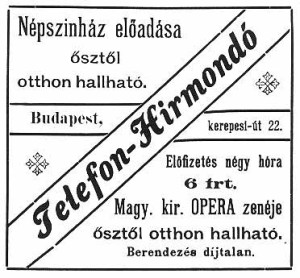

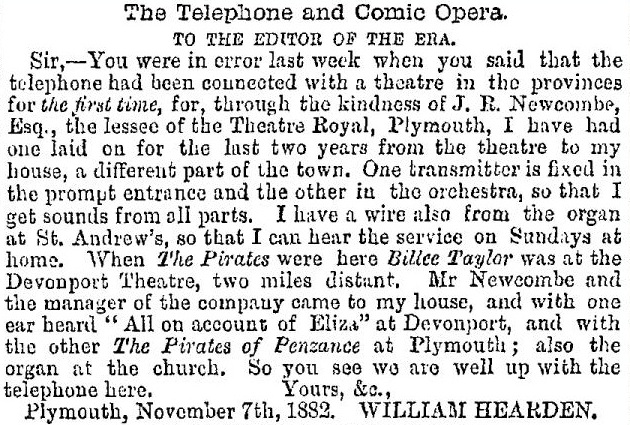

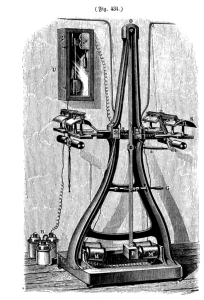

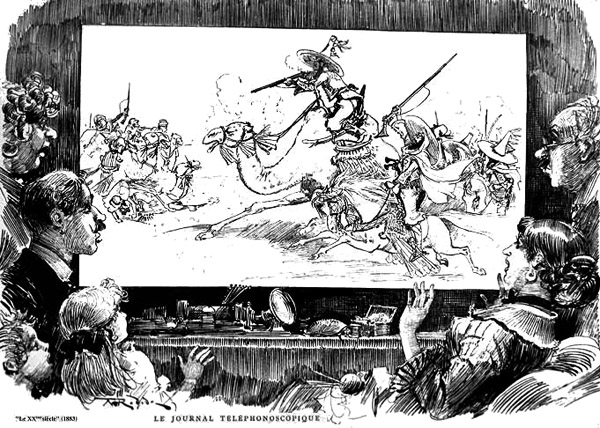

The first electronic medium able to carry sound was the telephone. In the opera world, it took off like wildfire:

– 1876 – New York Times article saying it could be used to carry opera to homes

– 1878 – First opera transmission

– 1878 – First opera transmission

– 1880 – First electronic home entertainment (opera)

– 1881 – First stereo-sound transmission (opera)

– 1882 – First payment for opera by phone

– 1885 – First pay-cable subscription (for opera)

– 1887 – First international media event (opera)

– 1888 – Consumer headphones for opera (might have been earlier)

– 1889 – First coin-operated entertainment (opera)

– 1893 – First newscast (created for opera-by-phone service)

I think one can’t help but wonder why this adoption occurred so fast. There’s a clue in that 1876 New York Times article.

It was published on March 22 of that year, before Alexander Graham Bell’s announcement. It said, “No man who can sit in his study with his telephone by his side, and thus listen to the performance of an opera at the Academy, will care to go to Fourteenth Street and to spend the evening in a hot and crowded building.”.

Today, you can attend operas at a theater near Stockholm called the Drottningholms Slottsteater (Drottningholm Court Theater). It was built in 1766 and, for various reasons, fell into disuse. Rediscovered in the 20th century, it needed only new rope for 18th-century stage machinery. With nothing but human power, it can effect a complete scene change in as little as four seconds. It has elevators, machinery for flying singers around, thunder and ocean effects, and more. You can watch a video of it in operation here: http://dtm.se/visningar/bakom_kulisserna.asp

Today, you can attend operas at a theater near Stockholm called the Drottningholms Slottsteater (Drottningholm Court Theater). It was built in 1766 and, for various reasons, fell into disuse. Rediscovered in the 20th century, it needed only new rope for 18th-century stage machinery. With nothing but human power, it can effect a complete scene change in as little as four seconds. It has elevators, machinery for flying singers around, thunder and ocean effects, and more. You can watch a video of it in operation here: http://dtm.se/visningar/bakom_kulisserna.asp

I found the opera house “hot and crowded” when I was there in mid-summer, but that was nothing compared to what the original patrons must have felt. As a concession to modern fire codes, an elaborate fiber optic system delivers the light of one candle to each former candle location used for stage lighting. Imagine when it was lit by candles.

In addition to heat, a candle would typically consume as much oxygen as two large people. Prior to the middle of the 19th-century, candles were also stinky, smoky, & sometimes toxic, and the wicks didn’t get consumed, so performers periodically had to snip them. Patrons sometimes complained that they couldn’t see performers through the smoke.

The audience section of the opera house never got completely dark. Wax would sometimes drip on the audience from chandeliers, and the light level has been described as equivalent to about one 75-watt bulb lighting the entire auditorium of the Drury Lane opera house.

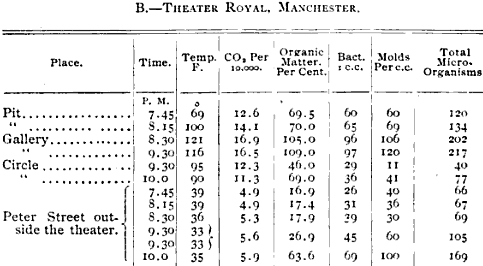

Oil and gas eliminated the dripping-wax problem, and gas could even be dimmed, but open flames still generated heat. Ventilating and Heating by John Shaw Billings, a book published by The Engineering Record in 1893, includes a study of Manchester’s opera houses. At the Theatre Royal, on a day and at a time when the temperature on Peter Street outside the opera house was 36 degrees Fahrenheit, the temperature in the gallery (a balcony seating area) was 121. At the same time, the carbon dioxide concentration on the street was 530 parts per million; in the gallery it was 1,690. There were also three times as many microorganisms in the gallery as on the street.

That was actually one of the better theaters. Its patrons tended not to die. But, in addition to sweating, they sometimes came close to freezing.

One reason they didn’t die is that the hot, low-oxygen, high-carbon-dioxide air was vented out the top of the building. But nature abhors a vacuum, so fresh air came in at the bottom; if it was freezing outside, it was almost as cold at some points inside.

Media? Hooray!

9. How Opera Drove Videodisc Subtitling (posted by Simon Hailes 2012 February)

I’ve worked for Screen Subtitling Systems since 1992. When I joined, I was surprised to find out about some of the more unusual uses for subtitles. At the time, videodiscs (12″) were on the wane for films, having had their day as a high quality but cumbersome medium, replaced by the much more commercial VHS. However, VHS did not have the bandwidth to carry much in the way of subtitles. The best they could do was a form of US Closed Captions, intended for own-language captions for the deaf. Videodisc, however, provided close to full PAL bandwidth, and so teletext data could be coded directly as part of the video, and had the capacity to carry multiple languages of subtitles.

We had one customer who basically had the market cornered for subtitling opera videodiscs, using the full multi-lingual capability of our systems to put as many as 16 languages of translation in a single VBI [vertical blanking interval]. It also highlighted differences in subtitling styles according to requirements, since, in general, people who purchased videodiscs of opera generally appreciated quality, their TV sets were generally large, and so single-height subtitles could be used, minimizing the area of the video covered when subtitles were on screen. This is still the only case where I’ve found single-height teletext used for subtitling regularly.

Comments:

Mark Schubin: When opera first appeared on LaserDisc, VHS was hugely outselling it in ordinary home-video releases. But the Met Opera’s LaserDisc sales were comparable to their VHS sales; buyers wanted the extra quality.

By the way, there’s quite a long history of (sub)titles for opera. Some opera historians think it began in 1983 with Canadian National Opera’s Surtitles. But, in 1976, the PBS telecast of Barber of Seville from New York City Opera in the Live from Lincoln Center series had live subtitles — thought to be the world’s first live television subtitles.

Then there was the British patent issued to Thomas Lloyd Jones and William Robert Lake. It “relates to apparatus for exhibiting the libretto of a performance simultaneously with its delivery.” It is patent 4267, issued October 1, 1881. It placed illuminated titles on a rolling, flexible medium on either side of a stage proscenium. The illumination came from gas jets!

Then there was the British patent issued to Thomas Lloyd Jones and William Robert Lake. It “relates to apparatus for exhibiting the libretto of a performance simultaneously with its delivery.” It is patent 4267, issued October 1, 1881. It placed illuminated titles on a rolling, flexible medium on either side of a stage proscenium. The illumination came from gas jets!

Patrick von Sychowski: I’d be interested to know if the VD/LD subtitles were re-used surtitles used on-stage of the live performance of the opera, and if so, what trans-coding was required. For home releases of feature films, I’ve been told that the same subtitles (whether foreign>English or English>foreign) could not be used from the cinema release as there was less character space on LDs/VHSs, so the text had to be shorter. Of course, this was most likely a feature of the smaller CRT sets of that time, as I’m sure longer text could be coded even for the sub-PAL low-res LD/VHS resolution.

Mark Schubin: I can report that the early Metropolitan Opera and New York City Opera television subtitles were created from scratch by subtitlist Sonya Friedman (neither opera company had any in-house titles at the time). The Met broadcast titles were used on their home-video releases. TV opera subtitles are about eight years older than in-house surtitles.

10. How Opera Helped Make Pelé a Sports Star (2012 February)

The year was 1958. The International Federation of Association Football (FIFA, based on its name in French) had scheduled its quadrennial World Cup for Sweden. Naturally, the national television broadcaster, Sveriges Radio Television (SVT), wanted to cover the matches live for the European Broadcasting Union’s Eurovision network. But there seemed to be a problem.

Although Eurovision, itself, wasn’t created until 1954, the first test transmissions of television in Sweden didn’t occur until after Eurovision’s first network transmission. Actual broadcasting (from what was then called Radiotjänst Television) didn’t begin until 1956, daily broadcasts didn’t begin until 1957, and regular news broadcasts not until September 2 of 1958, months after the FIFA World Cup was over. So Eurovision was appropriately concerned about the ability of SVT properly to cover the athletic contest, which would occur in different locations around the country. They needed a demonstration of SVT’s live remote capability. SVT provided one.

They broadcast live on Eurovision Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice from the tiny Drottningholms Slottsteater outside of Stockholm. The 18th-century opera house had no broadcast facilities, no television lighting, no air conditioning, and could go up in flames if treated improperly.

They broadcast live on Eurovision Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice from the tiny Drottningholms Slottsteater outside of Stockholm. The 18th-century opera house had no broadcast facilities, no television lighting, no air conditioning, and could go up in flames if treated improperly.

The opera remote broadcast was a success, so Eurovision gave the okay for SVT to cover the FIFA World Cup for them. In the final game, a 17-year-old player called Pelé scored two goals, winning the match for Brazil and leading even his opponent, Swedish player Sigge Parling, to say, “When Pelé scored the fifth goal in that final, I have to be honest and say I felt like applauding.” Then, overcome with emotion, Pelé fainted. All of it was captured live on television, thanks to opera.

Pelé’s real first name, by the way, is Edson. He is named after the American inventor Thomas Edison, whose work on the invention of motion pictures was intended specifically for opera and who predicted in 1891 that he would be able to show opera on color television at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. But that’s another story.

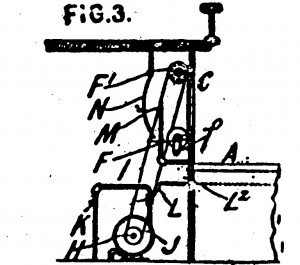

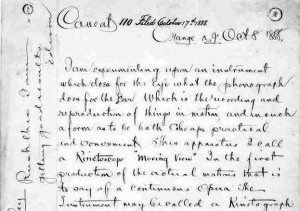

11. Edison, Opera, and Television (2012 March)

There’s a pretty famous quote about Thomas Edison bringing opera to homes in a new invention. The prediction, made on May 12, 1891, is generally thought to have been about motion pictures. There’s no question Edison invented motion pictures for opera; his 1888 patent caveat mentions nothing else as their purpose. But I’ve been analyzing his 1891 quote, and I believe he was predicting televised opera then, not movies (he wouldn’t be the first; there were televised-opera predictions in 1882 and 1877, too). For more on this, check out my blog post: https://staging.sportsvideo.org/blogs/?blog=schubin-cafe&news=what-it-was-was-television

There’s a pretty famous quote about Thomas Edison bringing opera to homes in a new invention. The prediction, made on May 12, 1891, is generally thought to have been about motion pictures. There’s no question Edison invented motion pictures for opera; his 1888 patent caveat mentions nothing else as their purpose. But I’ve been analyzing his 1891 quote, and I believe he was predicting televised opera then, not movies (he wouldn’t be the first; there were televised-opera predictions in 1882 and 1877, too). For more on this, check out my blog post: https://staging.sportsvideo.org/blogs/?blog=schubin-cafe&news=what-it-was-was-television

Comments:

Jim Lindner: But there is a real question as to whether Edison actually invented motion pictures – or perhaps better said – invented it first. This has been argued by historians for quite some time. I think it is fair to say that the consensus of opinion is that Charles Francis Jenkins is the inventor of what we came to know as Motion Pictures with his invention (along with Armat to some extent) of the Phantascope – the direct predecessor to the Edison Vitascope.

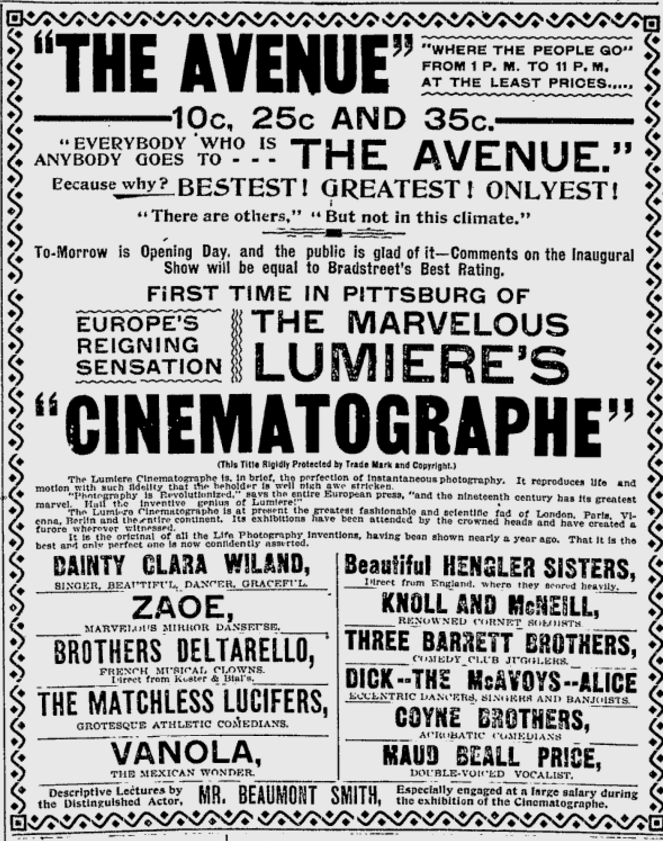

General consensus is that the inventor of the motion picture camera is Louis Le Prince although there were many other camera inventors working at the same time (Lumiere for example), and Le Prince’s camera was a bit dodgy. The one that first really worked was made by William Dickson who worked for Edison (and had access to the Phantascope information). As was the way at the Labs, Edison himself took credit for what was the work of Dickson and others – which was typical of many inventions ascribed to Edison.

General consensus is that the inventor of the motion picture camera is Louis Le Prince although there were many other camera inventors working at the same time (Lumiere for example), and Le Prince’s camera was a bit dodgy. The one that first really worked was made by William Dickson who worked for Edison (and had access to the Phantascope information). As was the way at the Labs, Edison himself took credit for what was the work of Dickson and others – which was typical of many inventions ascribed to Edison.

Don’t get me wrong – I am a big Edison fan, but the reality is that one of his largest contributions was not so much the individual inventions as much as his development of the lab system to invent – if you will he invented the way to invent in the modern way. Today, Dickson is generally given credit for the actual invention of the Vitascope camera.

Mark Schubin: You’re right, Jim. I should have used different language. What I meant to say was that whatever Edison did do in the creation of motion pictures, he did for opera. His initial patent caveat in 1888 specifies nothing but opera as the purpose of motion pictures.

As you point out, there’s no question that Edison was not the first person to come up with the concept of photographic motion pictures. But it might well be the case that whoever did did so for opera. You mentioned Jenkins and Le Prince. Here’s an excerpt from Jenkins’s 1925 book Vision by Radio, about his television work:

“The casing enclosing the mechanism is not very large, and contains, besides the radio vision mechanism, the radio receiving set, and a loudspeaker, so that an entire opera in both action and music may be received.”

Here is the famous quote about Le Prince’s work from the Secretary of the Paris Opera in 1890:

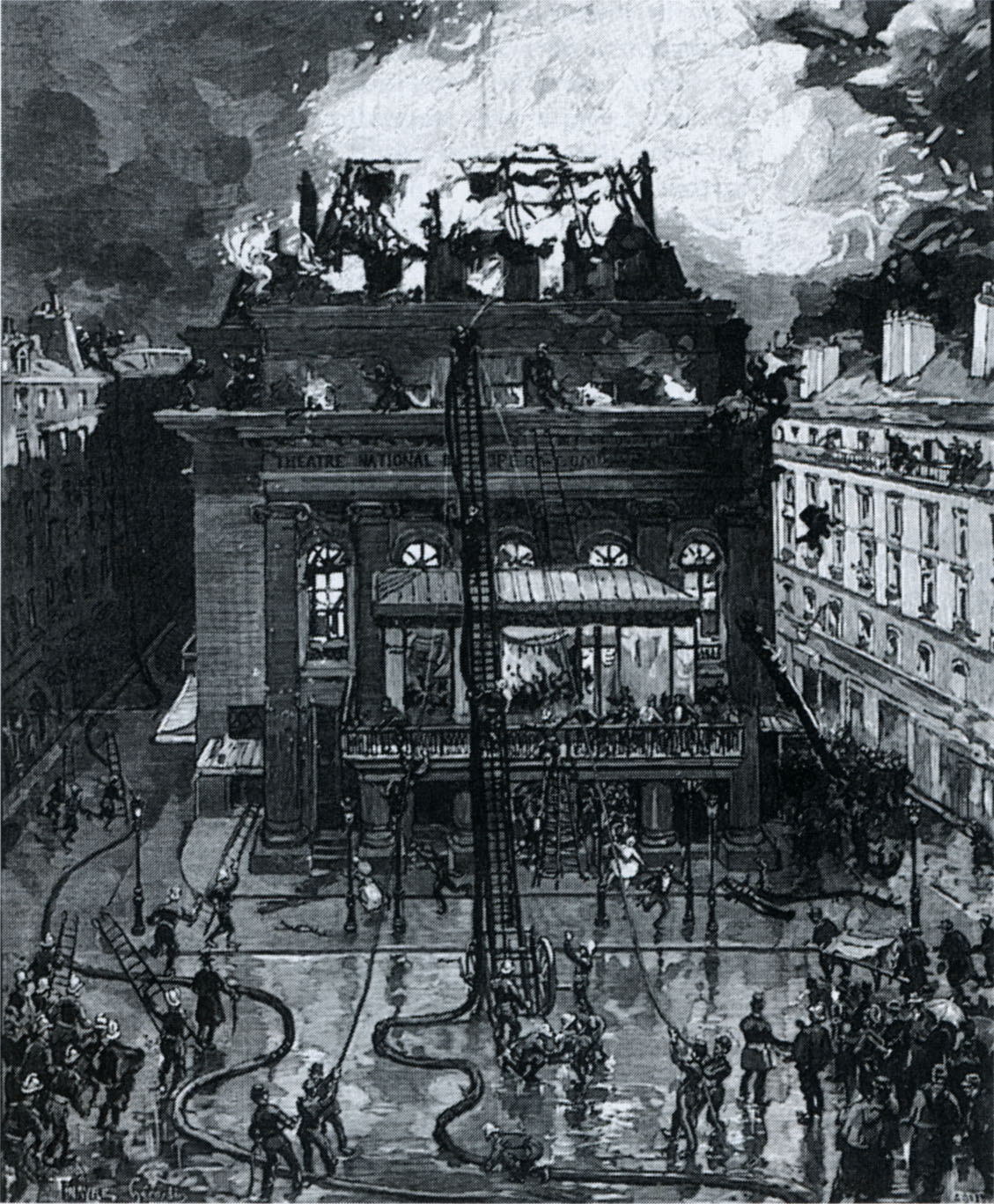

“I, the undersigned, Ferdinand Mobisson, Secretary of the National Opera, Paris, residing at 38 Rue de Mauberge, certify by this present to have been charged with the study (or examination) by means of the apparatus brought before me, of the system of projection of animated pictures, for which Mons. Le Prince, Louis Aime Augustin, of New York, United States, has taken out in France patent rights, dated the 11th of January, 1888, having the number 188,089, for ‘Method and Apparatus for the projection of Animated Pictures, in view of the adaptation to Operatic Scenes,” and to have made a complete study of the system, in faith of which I have delivered the present certificate to serve whom it may concern.”

The Lumiere brothers made opera movies and chose as the location of their first public showing the Grand Cafe near the Paris Opera. As for William Dickson, in the first (known) sync-sound movie, shot in 1894, he plays music from the opera Les cloches de Corneville on screen on his violin.

As you point out, what we consider “modern” movies came from these inventors, but all of them were preceded by others, such as Eadweard Muybridge. And Muybridge was preceded by Louis Jules Duboscq.

Who was Duboscq? In 1852, he was issued the world’s first patent for a photographic motion-picture projection system. It was also stereoscopic.

He happened also to be the head of special effects at the Paris Opera, where, three years earlier, he used electric light for a sunrise effect in the Meyerbeer opera, Le prophete, 30 years before Edison’s first light-bulb demonstration.

More interesting to me than the electric lighting was the power for it. Duboscq created a battery room in the basement of the opera. Unfortunately, the batteries of the day (Bunsen cells) emitted toxic fumes, so Duboscq had to create a system (praised by Nature magazine) to scrub the toxic chemicals from the air — all in the service of opera!

Jim Lindner: While the inventor’s intention at least for the patent application likely was opera, the practical reality of what happened was decidedly plebeian. Early cinema was almost entirely seen by the public in side show type entertainment, portrayed fairly accurately in Hugo.

The “plots” of the early Kinetoscope films were things like people kissing, dancing, and uh – boxing cats (no I did not make that up) and a wide variety of subjects definitely not operatic – at least not intentionally.

A list of extent early Edison films organized by date is available from the Library of Congress here as part of the now defunct “American Memory” project, and it is fun to look at some. There is quite a bit on YouTube as well: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/edhtml/edmvchrn.html

I believe this is the film you refer to. A very early 1895 (according to LOC not 1894) Dickson experiment with sound can be viewed here. As is obvious films were envisioned to be “sound” from the very beginning. Could he have been playing opera on the violin – perhaps! The horn’s size appears to not be that atypical from ones used in the day to record opera. Still – this film from 1894/5 was 4 years later than the first experiments by Dickson that were definitely MOS [without sound]: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mbrsmi/edmp.4034

I believe this is the film you refer to. A very early 1895 (according to LOC not 1894) Dickson experiment with sound can be viewed here. As is obvious films were envisioned to be “sound” from the very beginning. Could he have been playing opera on the violin – perhaps! The horn’s size appears to not be that atypical from ones used in the day to record opera. Still – this film from 1894/5 was 4 years later than the first experiments by Dickson that were definitely MOS [without sound]: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mbrsmi/edmp.4034

It took quite some time for cinematic language as we know it to evolve. Opera by contrast in 1891 already had a very long and deep tradition. Early film did not wade into those established waters for quite some time.

Mark Schubin: Although it’s certainly true that Edison did not achieve his goal of opera movies for some time, there were plenty of opera-movie conjunctions prior to the 20th century. Some think that Edison’s 1894 Carmencita was intended to be heard with music of Carmen. As for the 1894/5 Dickson experimental sound movie, you can listen to it with the opera music coming from his violin here (extract the Dickson file from the zip): https://staging.sportsvideo.org/wp-content/uploads-schubin/2011/11/LOC_Fandom_Files.zip

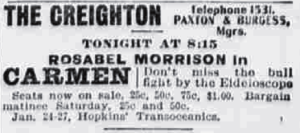

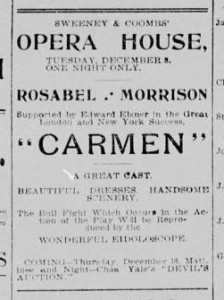

In 1896, Le Prince’s goal of adapting movies to operatic purposes was realized when the Rosabel Morrison Opera Company performed Carmen in a touring company with the movie Bullfight used as a backdrop in the last act; that touring opera was many Americans’ first experience of projected motion pictures (many of the shorts you describe were pre-projection). There were operetta movies shown in Europe the same year.

In 1896, Le Prince’s goal of adapting movies to operatic purposes was realized when the Rosabel Morrison Opera Company performed Carmen in a touring company with the movie Bullfight used as a backdrop in the last act; that touring opera was many Americans’ first experience of projected motion pictures (many of the shorts you describe were pre-projection). There were operetta movies shown in Europe the same year.

In 1897, just two years after their first public showing of movies, the Lumiere brothers released Georges Hatot’s Faust, based on Gounod’s opera. In 1898, a two-minute version of the opera La fille du regiment was released.

The same year, Flotow’s opera Martha was shot; it was shown the following year at the Eden Musee in New York, with singers behind the screen lip-synching to the performers being projected. Georges Mellies’s Cendrillon, based on the Massenet opera of the same name, was also released in 1899.

You can find many more examples of 19th-century opera movies in Ken Wlaschin’s Encyclopedia of Opera on Screen. And, in 1900, the last year of the 19th century, at the Paris World’s Fair, the Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre provided many sync-sound movies of opera arias.

Jim Lindner: And it was at that same 1900 Paris World’s Fair where Valdemar Poulsen exhibited the Telegraphone, the first working device to record on magnetic media. So, other than recording the voice of Emperor Franz Joseph, did Poulsen have any operatic aspirations for his invention? It would seem logical given the time period that opera was envisioned being recorded on this device as well.

Mark Schubin: That’s not an area I’ve researched yet (but, given that Poulsen was a telephone engineer, he might have been working on the answering machine). I look forward to learning more!

By the way, that Paris 1900 World’s Fair was one heck of a place for the introduction of media technology. Besides what we’ve discussed here (sync-sound movies and magnetic recording), it had large-format large-screen movies (precursor to IMAX) and motion-platform simulators (including one with a motion-parallax 3D effect), and it is where the word “television” was first publicly used.

By the way, that Paris 1900 World’s Fair was one heck of a place for the introduction of media technology. Besides what we’ve discussed here (sync-sound movies and magnetic recording), it had large-format large-screen movies (precursor to IMAX) and motion-platform simulators (including one with a motion-parallax 3D effect), and it is where the word “television” was first publicly used.

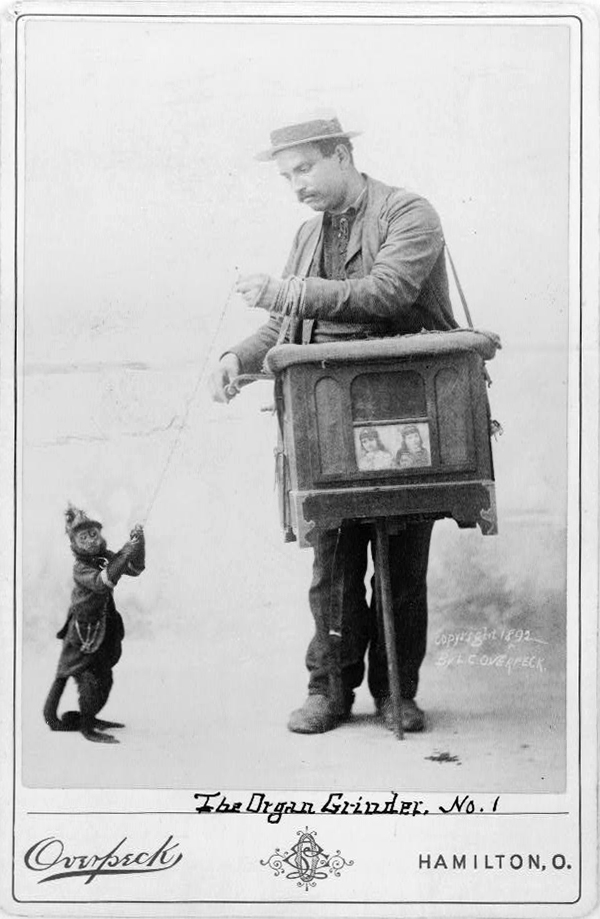

And, in the world of opera and media technology, it is where the first wireless opera broadcasts took place! Horace Short (an aviation pioneer who built the first aircraft factory and later designed the folding-wing planes used on aircraft carriers) came up with the idea of compressed-air amplification. During the Fair, he took one of his “auxeto-gramophones” to Gustave Eiffel’s office at the top of the Eiffel Tower and played opera recordings. The needle controlled a valve that controlled the compressed air so that the music could be heard over a large area on the ground.

Here’s a recent post I did on the 1900 Paris World’s Fair: https://staging.sportsvideo.org/blogs/?blog=schubin-cafe&news=smellyvision-and-associates

Another comment: Well, I haven’t yet found anything connecting Poulsen to opera, but Marvin Camras, who was issued more than 500 patents in the field of magnetic recording, built his first magnetic audio recorder to help a cousin who wanted to be an opera singer.

And another comment: I just (2013 March 19) discovered that, despite its being called an opera in many references, Rosabel Morrison’s Carmen was a play based on the Mérimée story, not an opera. Sorry!

12. Opera and Theatrical Television (2012 March)

I just posted a history of theatrical-television technology on SchubinCafe.com. It starts (in 1877!) and ends, of course, with opera: https://staging.sportsvideo.org/blogs/?blog=schubin-cafe&news=getting-the-big-picture

13. Opera and Alternative Content for Cinema — and Baseball (2012 March)

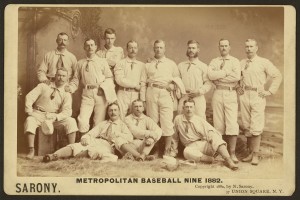

Here’s a link to the post of part II of the alternative-content-for-cinema story, with lots more about opera — and baseball. There has been a long relationship between baseball and opera, two of the things for which Cooperstown, New York is famous (the Baseball Museum and Hall of Fame and the Glimmerglass Festival operas).

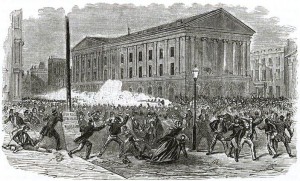

Consider, for example, the Astor Place Riot of May 10, 1849, New York City’s deadliest riot when it occurred. At first glance, it might seem to have had nothing to do with either baseball or opera, being, instead, a dispute between fans of the American actor Edwin Forrest and those of the British actor William Macready over who could better perform Macbeth. Macready was performing his version at the Astor Place Theatre, where the riot began. But the building had only recently been renamed; it was previously the Astor Opera House.

Consider, for example, the Astor Place Riot of May 10, 1849, New York City’s deadliest riot when it occurred. At first glance, it might seem to have had nothing to do with either baseball or opera, being, instead, a dispute between fans of the American actor Edwin Forrest and those of the British actor William Macready over who could better perform Macbeth. Macready was performing his version at the Astor Place Theatre, where the riot began. But the building had only recently been renamed; it was previously the Astor Opera House.

Nigel Cliff’s book The Shakespeare Riots (Random House, 2007) begins with the Forrest camp recruiting thugs from among the baseball players at the Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey, where “Three years earlier the first organized baseball match had been held….” And, according to his obituary in The New York Times, the person who rescued Macready from the murderous mob was the former opera-house impresario Edward P. Fry (who later became the inventor of electronic home entertainment when he arranged to listen to operas at home by telephone).

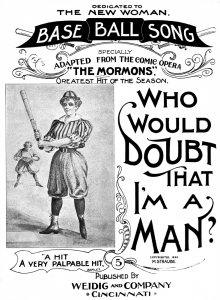

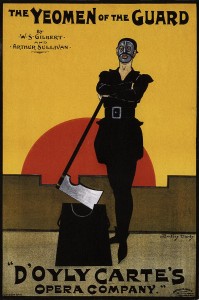

Then there is the famous baseball poem written by Ernest Thayer in 1888, “Casey at the Bat.” Its first recitation from the stage was by the comic-opera star DeWolf Hopper as part of the opera Prinz Methusalem that year. Hopper became the most famous performer of “Casey,” by some accounts having done it more than 40,000 times (he claimed only 10,000). The DeWolf Hopper Opera Company, by the way, performed an opera called Mr. Pickwick in 1903; in 1936, a different Pickwick became the first opera premiered on television. And, in 1953, William Schuman, who later became the first president of Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, turned the poem into the opera The Mighty Casey (which was, of course, performed at Glimmerglass in Cooperstown).

Then there is the famous baseball poem written by Ernest Thayer in 1888, “Casey at the Bat.” Its first recitation from the stage was by the comic-opera star DeWolf Hopper as part of the opera Prinz Methusalem that year. Hopper became the most famous performer of “Casey,” by some accounts having done it more than 40,000 times (he claimed only 10,000). The DeWolf Hopper Opera Company, by the way, performed an opera called Mr. Pickwick in 1903; in 1936, a different Pickwick became the first opera premiered on television. And, in 1953, William Schuman, who later became the first president of Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, turned the poem into the opera The Mighty Casey (which was, of course, performed at Glimmerglass in Cooperstown).

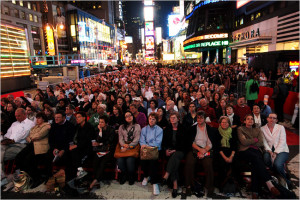

You’ll find some of the rest in the post. On August 23, 1914, a Coleman Life-Like Scoreboard was installed in the Providence Opera House so spectators could “watch” away baseball games (according to the Providence Evening News the next day, “Even arguments between players and arbitrators are shown”). Starting in 2007, San Francisco Opera began simulcasting Opera in the Ballpark to AT&T Park, home of the Giants, where not only the stands but also the outfield fills with tens of thousands of opera fans; the following year Washington National Opera sent its version, Opera in the Outfield, to Nationals Park.

Enjoy the post: https://staging.sportsvideo.org/blogs/?blog=schubin-cafe&news=the-alternatives

Comments: One more tidbit: The great operatic tenor, Enrico Caruso (who made the earliest recording to sell a million copies), was once asked what he thought of Babe Ruth. He said he couldn’t say because he’d never heard her sing.

Comments: One more tidbit: The great operatic tenor, Enrico Caruso (who made the earliest recording to sell a million copies), was once asked what he thought of Babe Ruth. He said he couldn’t say because he’d never heard her sing.

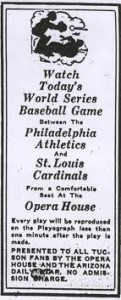

And another: The Tucson Opera House installed a Playograph scoreboard. According to a notice in The Arizona Daily Star, there was no admission charge to come and watch the 1931 World Series between the Philadelphia Athletics and the St. Louis Cardinals. It was “presented to all Tucson fans by the Opera House and” the newspaper.

Here’s a link to a baseball-opera chronology: https://staging.sportsvideo.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Opera-and-Baseball-Chronology.pdf

14. Opera and Lighting, Libretti, & Language (2012 April)

I attended a ballet at the 3800-seat Metropolitan Opera House this weekend. As usual, just before the performance began, the auditorium’s chandeliers rose to the ceiling.

The Met is New York City’s largest opera house. One of its tiniest used to be the Amato. There, too, two tiny hanging audience lights rose to the ceiling just before the performances.

Both theaters were offering a historical echo of what must have happened in opera’s early days, when lighting — both on stage and in the auditorium — came from candles and oil lamps. Those had to be lit, so, before each performance, chandeliers would have had to have their candles lit in the ceiling, be lowered to light the auditorium, and then be raised for the performance.

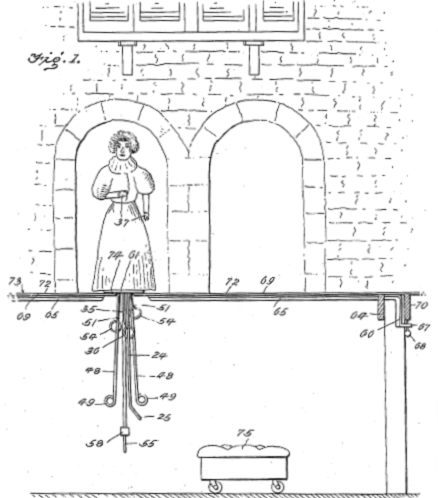

Lighting could be pretty elaborate even back in the old days. The second edition of Nicola Sabbattini’s handbook of stagecraft, published in 1638, includes instructions for and a diagram of a light-dimming system, as well as information on house lighting, lightning-bolt effects, and color filters. Michael Callahan’s 2006 “Automated Lighting: The Backstory” notes that “in the days when audiences were still wearing powdered wigs,” the “French changed the color of candlelight using long cords to swap panels of dyed silk.”

Lighting could be pretty elaborate even back in the old days. The second edition of Nicola Sabbattini’s handbook of stagecraft, published in 1638, includes instructions for and a diagram of a light-dimming system, as well as information on house lighting, lightning-bolt effects, and color filters. Michael Callahan’s 2006 “Automated Lighting: The Backstory” notes that “in the days when audiences were still wearing powdered wigs,” the “French changed the color of candlelight using long cords to swap panels of dyed silk.”

It might be worth noting that “candlelight” was very different before the mid-19th-century from what it is today. Michael Faraday’s lectures on “The Chemical History of a Candle” were given in 1860, by which time candles were not too different from today’s. Before that, however, they would typically have been dim, smoky (there are reports of so much haze as to prevent the performers from being seen), stinky, and sometimes toxic. Those in chandeliers could easily (because they were softer than today’s) drip hot wax on the audience below. They could be expensive, so few would be used. And their wicks didn’t get consumed, so they would grow to the point of danger, requiring actors and singers to trim them as they moved about the stage.

Aside from toxicity, lighting sources through the end of the 19th century (candles, oil lamps, and various forms of gas lighting) produced significant heat and often caused fires. A study of an opera house in Manchester, England, published in 1893, showed that, at a time when the temperature on the street was 36 degrees Fahrenheit, it was 121 in the upper seating. The carbon-dioxide level in the coal-fired, Industrial-Age street was 530 parts per million; in the house it was 1690. Bacteria, mold, and other organic hazards were also considerably higher inside than out. And drafts caused by venting the heat caused some audience members to complain of cold.

Aside from toxicity, lighting sources through the end of the 19th century (candles, oil lamps, and various forms of gas lighting) produced significant heat and often caused fires. A study of an opera house in Manchester, England, published in 1893, showed that, at a time when the temperature on the street was 36 degrees Fahrenheit, it was 121 in the upper seating. The carbon-dioxide level in the coal-fired, Industrial-Age street was 530 parts per million; in the house it was 1690. Bacteria, mold, and other organic hazards were also considerably higher inside than out. And drafts caused by venting the heat caused some audience members to complain of cold.

What does all of this have to do with opera and media-technology? The opera part is that many lighting advances came from opera, from 16th-century color filters to 17th-century dimmers to 18th-century projection to 19th-century gas and then electric lighting to 20th-century automated lighting (Callahan attributes “the first automated lighting system” to Fritz von Ballmoos, a Swiss low-temperature physicist with “an interest in opera and no prior connection to entertainment lighting”). As for the media, there are both media-philosopher Marshall McLuhan’s description of light as a medium and, more significant here, the fact that lighting enabled the use of another operatic medium: print.

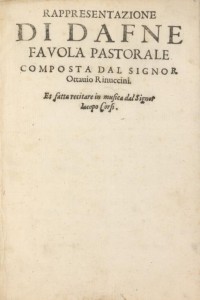

Many say the first opera was Dafne, performed in Florence in what we’d today call 1598 (The New York Times recently reported — in its “Home” section — that the theater space still exists). The opera’s host printed little books (“libretti” in Italian) to give away as souvenirs to those in attendance (you can touch one at the New York Public Library’s Performing Arts Library). By 1600, the same libretto was reprinted as something to be bought, and that was well before the first opera ticket was sold, in 1637.

Many say the first opera was Dafne, performed in Florence in what we’d today call 1598 (The New York Times recently reported — in its “Home” section — that the theater space still exists). The opera’s host printed little books (“libretti” in Italian) to give away as souvenirs to those in attendance (you can touch one at the New York Public Library’s Performing Arts Library). By 1600, the same libretto was reprinted as something to be bought, and that was well before the first opera ticket was sold, in 1637.

There seem to be differences of opinion about whether people actually read libretti during early opera performances. For one thing, with only a few candles, the interiors of the opera houses were pretty dim.

I went to an opera at the 18th-century Drottningholms Slottsteater near Stockholm, and, although they’ve switched to electric lighting, they’ve tried to make it similar to what would have existed in the days of candles. The house lights stay on all the time, because the candles would have remained lit. Despite that, it was almost impossible to read anything, and, to comply with safety regulations, light-equipped ushers had to stay near the exit doors, which might otherwise be invisible. One lighting historian estimates that the total light output in London’s Drury Lane opera house would have been roughly equivalent to that of a single 75-watt incandescent bulb.

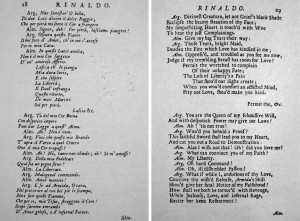

Things changed in 18th-century London, however, when composer George Frideric Handel introduced the opera Rinaldo in 1711. It was in Italian but intended for (and premiered in) an Anglophone city. So it had a bilingual libretto, with the Italian words printed on one side and their English translation facing them. That almost required the purchase of a libretto.

Things changed in 18th-century London, however, when composer George Frideric Handel introduced the opera Rinaldo in 1711. It was in Italian but intended for (and premiered in) an Anglophone city. So it had a bilingual libretto, with the Italian words printed on one side and their English translation facing them. That almost required the purchase of a libretto.

As for reading it in a dim theater, Mark Stahura’s “Handel’s Haymarket Theater,” in the 1998 Amadeus Press book Opera in Context, finds a reference in Henry Fielding’s 1751 novel Amelia. Stahura writes, “the heroine sits in the first row of the first gallery” where “she meets an amiable gentleman, who procures and holds a candle to facilitate her heading of the libretto.” Other reports indicate that those in the cheap seats (who, presumably, couldn’t afford either libretto or reading candle) would spit on the candles below, which they found a distraction from the action on stage.

In the previous post on subtitling, you’ll find info on alternatives to libretti, including an 1881 patent on a gas-jet illuminated text-display system. Of course, that, too, might be considered distracting.

15. Opera, Live Television, and John Goberman (2012 April)

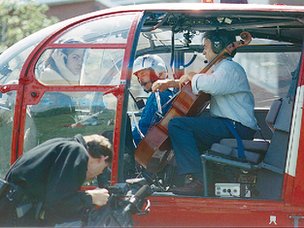

Lincoln Center announced on Friday that John Goberman, who created the Live from Lincoln Center series and produced it for its 37 seasons to date, will be leaving at the end of the month. Even before Live from Lincoln Center began, Goberman (formerly a cellist in the Metropolitan Opera orchestra) racked up a string of successes in media-technology and opera history:

Lincoln Center announced on Friday that John Goberman, who created the Live from Lincoln Center series and produced it for its 37 seasons to date, will be leaving at the end of the month. Even before Live from Lincoln Center began, Goberman (formerly a cellist in the Metropolitan Opera orchestra) racked up a string of successes in media-technology and opera history:

– 1970: plans for a subscription-television service offering opera

– 1971: first transmission of opera exclusively on cable TV; first use of low-light-level cameras for opera

– 1972: first proposed delivery of opera with stereo sound; first set-top box intended for opera

– 1973: first experiments in invisible television pickup of opera

– 1974: experiments in anamorphic and camera-stitched widescreen opera; viewer testing of the importance of stereo sound for opera

– 1975: exhibition of solid-state cameras, video disks, portable (and laser) video projection, and small-aperture satellite earth stations in the service of opera; commencement of work on a “contrast compression” circuit for live video to enable operatic spotlights and shadows to coexist

– 1976: Lincoln Center’s first (and, thus far, only) patent, for a secure-television system offering stereo sound

After Live from Lincoln Center began, the media-technology-and-opera hits continued, with the first nationwide live television transmission with stereo sound (and the first FCC tariffs for satellite transmission of stereo sound) and what I believe to be the world’s first live subtitles, both in 1976. Goberman also produced the first Live from the Met opera transmissions and taught delegations from all over the world about how to shoot live opera.

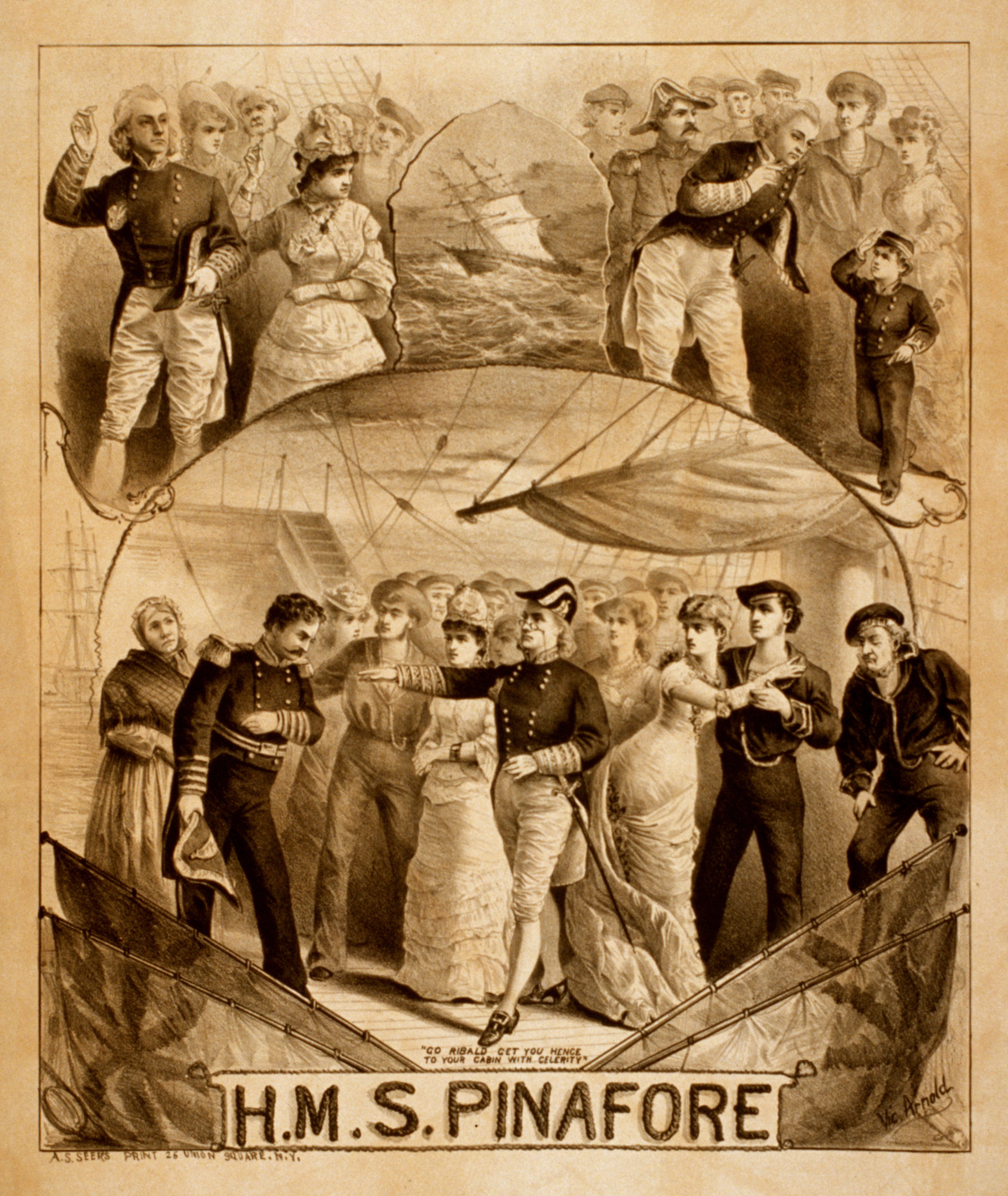

He was by no means the first to put opera on television. In 1934, the BBC telecast a highly condensed version of Carmen. In 1936, they carried portions of the opera Pickwick before it opened on stage, and, the following year, they telecast the first complete, uncut opera, La serva padrona. The BBC telecast an opera they commissioned, Cinderella, in 1938, but it had been commissioned for radio and adapted for television. The first opera commissioned specifically for television was Amahl and the Night Visitors, first aired by NBC in 1951.

That opera was directed by Kirk Browning, who worked for NBC Opera Theater, an opera company maintained by that television network for 16 years (they even went on tour starting in 1956). John Goberman hired Kirk Browning to direct Live from Lincoln Center, which Browning did until his death in 2008 at age 86.

That opera was directed by Kirk Browning, who worked for NBC Opera Theater, an opera company maintained by that television network for 16 years (they even went on tour starting in 1956). John Goberman hired Kirk Browning to direct Live from Lincoln Center, which Browning did until his death in 2008 at age 86.

NBC Opera Theater commissioned many new operas (not counting operas NBC commissioned for radio); so did CBS Television and ABC Television. Even two commercial U.S. TV stations (not networks), WAVE-TV and WBAL-TV, commissioned operas. And, besides the commissioned operas, all four U.S.commercial networks of the time (including DuMont) carried other opera programming.

Almost all of the above, however, was studio-shot programming. When the NBC Opera Theater team went to public television, they still produced studio-shot opera.

There had been some televised opera transmitted live from the stage. The first was by the BBC in 1947, the second by ABC in the U.S. in 1948. As recently as the late 1960s, however, when opera was shot from the stage, it almost might as well have been in a studio. Light levels soared. Cameras were mounted on platforms in the middle of the seating. Staging was adjusted for television needs. It was definitely not a typical live-opera experience.

That’s where Goberman came in. His mantra for the television team was “We are transmitting an opera, not producing it.” He wanted his cameras and microphones to be invisible, and there was to be no interference with the performers, the staging, or the audience. That’s why broadcasters from around the world came to Goberman to learn how to transmit opera performances on television, not how to shoot television operas.

How did it all work out? Aside from multiple Emmy and Peabody awards and other honors and some of the highest ratings on PBS, “Live from Lincoln Center” is in its 37th season.

Thanks, John!

For a bit more, here’s something I wrote on Friday on my blog: https://staging.sportsvideo.org/blogs/?blog=schubin-cafe&news=goberman-leaving-lincoln-center

16. More Baseball & Opera (2012 April)

I just did a little story for the Cooperstown Freeman’s Journal (more than 203-years old and still going strong). Here’s a link: http://issuu.com/allotsego/docs/allotsego-4-13-12?mode=window&viewMode=singlePage

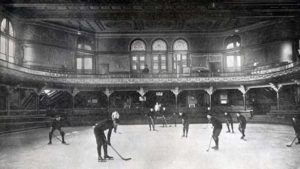

Not a lot of it is about media, but I have now traced telegraph-dispatch baseball games “performed” in opera houses back to 1885 in Augusta, Georgia and Nashville, Tennessee, spreading to many cities the following year. In the Detroit system, when there was a fly ball, a picture of a fly was projected.

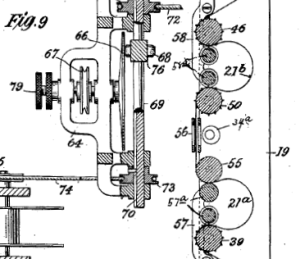

Here’s a patent issued in 1895 for a system already in use in many opera houses that year: http://www.google.com/patents/US543851

Here’s a patent issued in 1895 for a system already in use in many opera houses that year: http://www.google.com/patents/US543851

There must have also been a more elaborate version, because a contemporary newspaper account refers to “the coachers” clapping and dancing when there was a hit.

And here’s a bit more on Caruso and Babe Ruth: They both lived in the same New York City “hotel,” along with many other opera singers (among them Feodor Chaliapin, Geraldine Farrar, Lauritz Melchior, Ezio Pinza, Lily Pons, Eleanor Steber, and Teresa Stratas). Gambler Arnold Rothstein also lived there (the Ansonia), and that location, too, had a telegraphic baseball scoreboard, associated the 1919 World Series (the Ansonia is where the “Black Sox” scandal originated).

Comments: I’m doing a piece on watching baseball games remotely before television. It will appear in the Fall issue of Sports Tech Journal <http://www.hpaonline.com/assets/2013presentations/2013_tr_pres_mschubin_sportstechjournal.pdf> I don’t want to give too much away, but opera plays a significant role. One of the first places where people could watch baseball games remotely before television was at Nashville’s Grand Opera House in 1885. It quickly spread to opera houses across the country.

Of course, turnabout is fair play. Starting in 2007,San Francisco opera began simulcasting its operas to the giant LED scoreboard screen at the AT&T Park ball field, followed by the Washington National Opera at Nationals Park. On September 24, 2010, 32,000 people watched “Aida” live at AT&T Park.

Frank Zamacona: Hi Mark, I directed that Aida for the 31 feet high by 103 feet wide screen at AT&T Ball park. Just got back from Seattle directing their first Live HD Simulcast of Madama Buttterfly at the Key Arena where the screen was 50 feet wide by 80 feet high. It was bigger than their proscenium.

17. Opera and the First Wireless Sound Broadcast (June 2012)

If you study aviation history, you will almost certainly come across the name Horace Short, who, with his brothers, made Shorts aircraft and built the world’s first aircraft factory. Naval historians might know that he came up with the folding-wing design used to increase storage on aircraft carriers (though it was originally intended to allow sea planes to get close to docks).

If you study aviation history, you will almost certainly come across the name Horace Short, who, with his brothers, made Shorts aircraft and built the world’s first aircraft factory. Naval historians might know that he came up with the folding-wing design used to increase storage on aircraft carriers (though it was originally intended to allow sea planes to get close to docks).

I will say no more about those aspects of his life, nor will I discuss how he became king of a South Pacific tribe of cannibals or kept bandits from his Mexican silver mine by conveying the impression that he had super powers. No, here I will present only one tiny aspect of his life, the world’s first wireless broadcast of sound, which was opera.

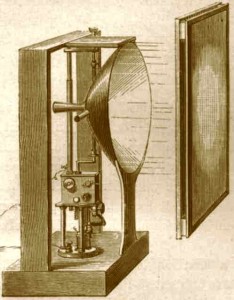

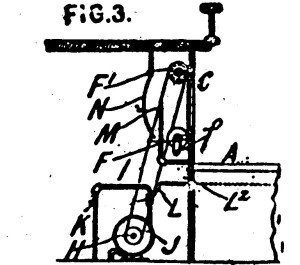

In 1898, Short applied for a patent on a sound-amplification device — effectively a powered megaphone. What’s particularly interesting about it is that 1898 was years before the first electronic amplification device. Short’s system didn’t need to use electricity at all; it used compressed air, the sound pressure of the voice moving a valve.

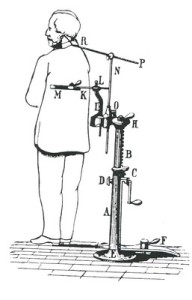

A second patent suggested that the amplification system could be used not merely as a megaphone but also for amplifying records, the valve controlled by a needle (Figure 6 of British patent 677,476, applied for April 29, 1899, issued July 2, 1901). To demonstrate it (possibly to gather publicity for the sale of his patents to turbine pioneer Charles Parsons), Short chose the Paris World’s Fair of 1900. And what more iconic spot there than Gustave Eiffel’s own room at the top of his tower (built for the previous Paris World’s Fair)?

A second patent suggested that the amplification system could be used not merely as a megaphone but also for amplifying records, the valve controlled by a needle (Figure 6 of British patent 677,476, applied for April 29, 1899, issued July 2, 1901). To demonstrate it (possibly to gather publicity for the sale of his patents to turbine pioneer Charles Parsons), Short chose the Paris World’s Fair of 1900. And what more iconic spot there than Gustave Eiffel’s own room at the top of his tower (built for the previous Paris World’s Fair)?

What records to play? That World’s Fair also featured synchronized-sound movies at the Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre of opera stars singing arias, so that’s what Short played, too. He later repeated the performance at Britain’s Blackpool Tower.

The compressed-air amplification was sufficient for the sound to be heard on the ground at a radius of at least a quarter mile from the tower. No, it wasn’t radio (though 20 years later the first off-air radio recording would be made at the Eiffel Tower, and it, too, would be of opera), but it was a wireless sound broadcast.

Comments:

Niels Windfeld Lund: Interesting, do you have a list of what arias he played ?

Mark Schubin: Not yet, but at the Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre at the same 1900 Paris World’s Fair Victor Maurel sang arias from Falstaff and Don Giovanni, Emile Cossira sang an aria from Romeo et Juliette, and a singer from La Scala by the name of Polin sang an aria from La fille du regiment.

I’m still searching for Short’s content.

18. Opera and Television – Canada Day Special (2012 July 1)

To celebrate Canada Day, consider naturalized-Canadian soprano Sarah Fischer, who performed the role of Carmen in the first televised opera, broadcast by the BBC on 1934 July 6 (using 30-line mechanical scanning).

19. The Earliest Opera Recordings (2012 July)

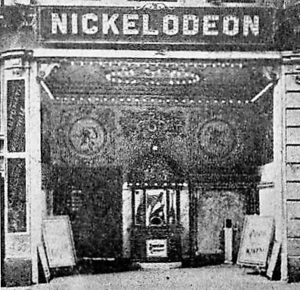

Good arguments can be made that opera played a major role in the development of (in rough chronological order), electronic home entertainment, stereo sound transmission, pay cable, movies, headphones, newscasts, sound movies, and even broadcasting — but not recording. When Thomas Edison described the uses of his phonograph shortly after its introduction in 1877, number one was letter writing.

It makes sense. Sound recordings couldn’t handle opera’s duration, and the large stage and moving singers were problems, too. And fidelity was far from high.

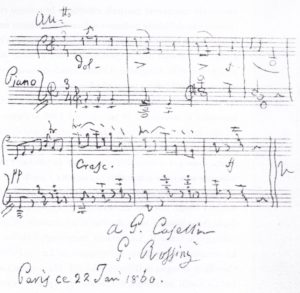

So, when was the first sound recording of opera music? Would you believe 1860 — 17 years before Edison’s first phonograph?

So, when was the first sound recording of opera music? Would you believe 1860 — 17 years before Edison’s first phonograph?

For this extraordinary discovery, I rely entirely on the experts at FirstSounds.org (and they are definitely experts). The recordings (and note the plural) were Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville’s phonautograms and were probably never intended to be played back. “Virtual stylus” technology developed at Lawrence-Berkeley National Laboratory allowed the first phonoautogram playback in 2008, and they’ve been improved since. The recording of “Au clair de la lune” is very clearly recognizable. Unfortunately, I can’t say the same for the opera recordings, which you’ll find on this page of the First Sounds site: http://www.firstsounds.org/sounds/scott.php/

They say it’s “La Chanson de l’Abeille” from the comic opera La Reine Topaze by Victor Massé, first performed in 1856. I’ll take their word for it. I’ve listened to both versions, and about the best I can come up with from personal listening is that it does sound like a human voice.

Those are the earliest known opera recordings. But there was much earlier opera playback! Yesterday, I got to hear one from around 1830! I’ll describe that in another post.

20. More on the Baseball-Opera Hotel (2012 July)

I’ve written a bit here about the baseball-opera residential hotel, the Ansonia, which had a telegraphic game-display system used to view the 1919 World Series. A party there Saturday inspired me to offer a little more.

I’ve written a bit here about the baseball-opera residential hotel, the Ansonia, which had a telegraphic game-display system used to view the 1919 World Series. A party there Saturday inspired me to offer a little more.

On the baseball side, the Ansonia’s most-famous resident was Babe Ruth, who reportedly entertained in his rooms every night and would sometimes play the saxophone (which he took up after moving in). That was not a problem inside his apartment (some of the walls were three feet thick); it was more noticeable when he played in the hallways. He’d also wear his red silk bathrobe to the basement barber for his morning shave.

There’s an exhibit of Babe Ruth artifacts in the current lobby. I recommend entering from the West 73rd Street entrance, just west of Broadway, which has a little of the old carriageway left. The exhibit is opposite the reception desk.

Besides Babe Ruth, other baseball players who lived at the Ansonia included “Sleepy Bill” Burns, Jean Dubuc, Bob Meusel, Lefty O’Doul, and Wally Schang. Visiting players (including Ty Cobb) also often lodged there, where the 1919 “Black Sox” scandal originated. Ray Chapman was staying at the Ansonia the day he was fatally hit by a pitch, the only player in Major League Baseball history to have been killed that way. Baseball’s first agent, Christy Walsh, started there.

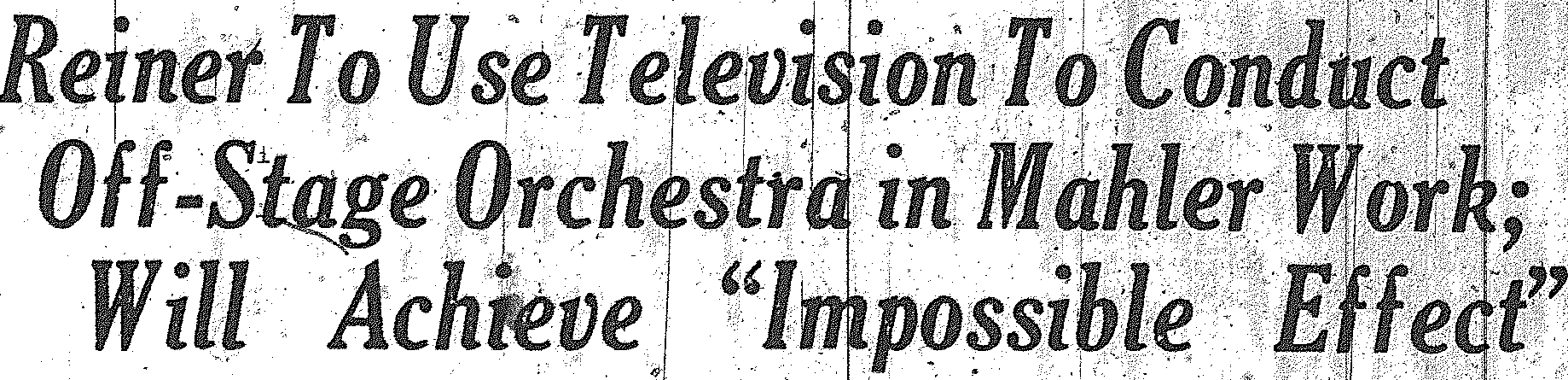

On the opera side, the Ansonia’s most-famous resident was reportedly Enrico Caruso (some dispute his living there, but it’s certainly possible that he spent at least one night). Others included Karin Branzell, Bruna Castagna, George Cehanovsky, Fyodor Chaliapin, Fausto Cleva, Alessio De Paolis, Geraldine Farrar, Giulio Gatti-Casazza, Gustav Mahler, Lauritz Melchior, Ezio Pinza, Lily Pons, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Elisabeth Rethberg, Bidu Sayao, Tito Schipa, Eleanor Steber, Teresa Stratas, Arturo Toscanini, and Thelma Votipka (who sang more performances at the Metropolitan Opera than any other woman). Like Babe Ruth, Melchior could sometimes be found in the long, wide hallways, in his case practicing archery on animal-trophy targets.