Truth Will Out

Story Highlights

A Capitol Fourth is one of the longest-lasting shows on PBS and is said to be the highest rated. It’s an extraordinary undertaking, with stars from virtually every genre of music performing live both in front of a huge crowd on the west lawn and steps of the U.S. Capitol building and, simultaneously, on TV stations across the country. On the engineering end, the show entails an enormous performance tent for the National Symphony Orchestra, giant screens, transmission links for cameras as far as kilometers away, audio setups for different performers on different stages (ranging from soft-voiced singers to marching bands to the cannons that punctuate Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture). The credits even include a meteorologist, who determines whether it’s safe for the show to go on.

On July 4 this year, the weather was safe but not good. Host Tom Bergeron kept hyping the upcoming fireworks, and an on-screen graphic noted the minutes and seconds to go before the first blast. Unfortunately, the cloud ceiling was low, and little more could be seen of the starbursts than a colored glow in the sky. So the show resorted to clearer pre-recorded fireworks, creating a minor scandal. A tweet from the show’s account said, in part, “It was the patriotic thing to do.”

That’s probably true. After the second Continental Congress passed the resolution of independence, John Adams wrote to his wife, Abigail, that that glorious “Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. I am apt to believe it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance…. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations… from this Time forward forever more.” So fireworks (“illuminations”) are part of the patriotic commemoration.

That’s probably true. After the second Continental Congress passed the resolution of independence, John Adams wrote to his wife, Abigail, that that glorious “Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. I am apt to believe it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance…. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations… from this Time forward forever more.” So fireworks (“illuminations”) are part of the patriotic commemoration.

There’s just one problem: Adams sent his letter to Abigail on July 3, which was the day after the resolution of independence was passed, “The Second Day of July 1776.” That was “independence day.” What happened on July 4 was just the approval of the wording of the commonly read declaration. Those complaining about the old fireworks in A Capitol Fourth didn’t seem to care that the actual 240th anniversary of U.S. independence occurred two days earlier.

The history of television technology is more obscure than the history of the United States, but it, too, has its erroneous myths and legends. Years before all-electronic television was “introduced” at the New York World’s Fair in 1939, for example, it had already been broadcast in London. Long before that, the first regularly scheduled television news broadcasts began in Schenectady, New York, using so-called “mechanical” scanning. Philo Farnsworth demonstrated the first scanned, all-electronic television system, but even that idea was published much earlier by someone else. And, if the term “scanned” is dropped, the first crude all-electronic television images were seen no later than 1879 (though the word television wasn’t coined until 1900).

The history of television technology is more obscure than the history of the United States, but it, too, has its erroneous myths and legends. Years before all-electronic television was “introduced” at the New York World’s Fair in 1939, for example, it had already been broadcast in London. Long before that, the first regularly scheduled television news broadcasts began in Schenectady, New York, using so-called “mechanical” scanning. Philo Farnsworth demonstrated the first scanned, all-electronic television system, but even that idea was published much earlier by someone else. And, if the term “scanned” is dropped, the first crude all-electronic television images were seen no later than 1879 (though the word television wasn’t coined until 1900).

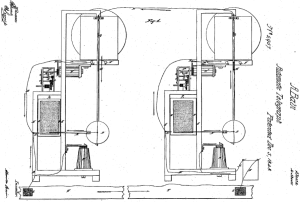

When did television start? It’s really impossible to say. It depends on definitions of television and start, among other things. The concept of scanning for image transmission was patented in 1843 by Alexander Bain, which the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences recognized with an Emmy award this year. That’s one important principle of television. Even more important, perhaps, is the concept of converting variations in light intensity into an electronic video signal—opto-electronic transduction.

When did television start? It’s really impossible to say. It depends on definitions of television and start, among other things. The concept of scanning for image transmission was patented in 1843 by Alexander Bain, which the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences recognized with an Emmy award this year. That’s one important principle of television. Even more important, perhaps, is the concept of converting variations in light intensity into an electronic video signal—opto-electronic transduction.

Few television histories mention the discovery of a photoelectric effect by 19-year-old Edmond Becquerel in 1839. That’s actually as it should be. Although Becquerel’s discovery was published at the time in major scientific journals, no one seemed to know what do do with it. When Becquerel, himself, demonstrated an electrical image transmission system to the French Academy of Sciences two decades later, he did not suggest any optical input for it; the images had to be drawn in insulating ink on a conductive surface.

Many television histories mention Joseph May, Willoughby Smith, and George R. Carey, and all are significant but not necessarily for who they supposedly were, what they are said to have done, or when they allegedly did it. May has been called an Irish telegraph clerk. That description probably stems from a report in Nature of a lecture given by Charles William Siemens to the Royal Institution of London in 1876—a very important talk. According to the report, knowledge of the photoconductivity of selenium was the result “of an observation made first by Mr. May, a telegraph clerk at Valentia,” Ireland. Siemens did attribute the observation to May and did put it in Valentia, but he never called him a clerk.

Many television histories mention Joseph May, Willoughby Smith, and George R. Carey, and all are significant but not necessarily for who they supposedly were, what they are said to have done, or when they allegedly did it. May has been called an Irish telegraph clerk. That description probably stems from a report in Nature of a lecture given by Charles William Siemens to the Royal Institution of London in 1876—a very important talk. According to the report, knowledge of the photoconductivity of selenium was the result “of an observation made first by Mr. May, a telegraph clerk at Valentia,” Ireland. Siemens did attribute the observation to May and did put it in Valentia, but he never called him a clerk.

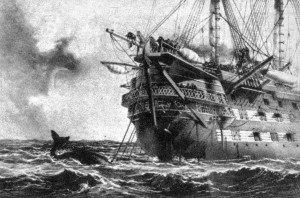

In fact, May, who had previously served as an assistant to the “electrician” (what we would today call electrical engineer) in charge of the laying of the first transatlantic telegraph cable, was in 1866 put in charge of the electrical department of the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company (Telcon) at the factory in Greenwich, England, where the second transatlantic cable had been manufactured. During the laying of the first cable, May served on the cable ship Agamemnon; for the second, he was at the European terminus in Valentia, while his boss, Willoughby Smith, served on the cable ship Great Eastern.

After the failure of the first cable, Smith was charged with ensuring the health of the second. A cable—even one made of copper—thousands of kilometers long has a high resistance, so Smith wanted a comparably resistive material for making his measurements. After trying layers of tinfoil separated by gelatine and finding the combination unstable, Smith decided to try crystalline selenium.

After the failure of the first cable, Smith was charged with ensuring the health of the second. A cable—even one made of copper—thousands of kilometers long has a high resistance, so Smith wanted a comparably resistive material for making his measurements. After trying layers of tinfoil separated by gelatine and finding the combination unstable, Smith decided to try crystalline selenium.

We might never know why Siemens attributed the discovery of selenium’s photoconductivity to May. Those who attribute it to Smith can use his own writing as a reference. “In my experiments with this substance, I was at first sorely puzzled” about its changing resistance, he wrote. “On investigation, this proved to be owing to the resistance of selenium being affected by the slightest variation in the rays of light falling upon it.”

They were his experiments, because he designed them. But he had his staff conduct them. According to the most recently available information, the discovery was actually made in 1872 by Telcon worker John E. Mayhew at the company’s facility at Enderby Wharf, Greenwich, where the company, its predecessors, and its successors have continuously been manufacturing underwater cables since 1857 (and, for six years before that, next door). It is currently operating as Alcatel-Lucent Submarine Networks (below). Mayhew informed May who informed Smith of the discovery.

Smith deserves his place in television histories. Not only did he choose to test selenium and design experiments to prove its photoconductivity (as opposed to, say, sensitivity to heat or current), but he also chose to inform the world about it. On February 4, 1873, he sent a letter to Latimer Clark, a colleague in the Society of Telegraph Engineers (today the Institution of Engineering and Technology), and asked him to read it at a society meeting. It set off almost a chain reaction as scientists and engineers tried to prove or disprove Smith’s findings.

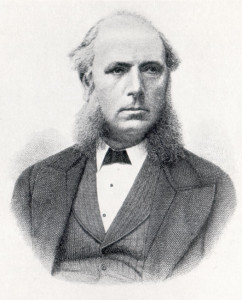

One of those was Werner von Siemens, William’s brother. On February 18, 1876, almost exactly three years after Smith’s findings were reported, William gave that fateful lecture to the Royal Institution about his brother’s work. And, at the end of it, he showed something that precipitated the advent of television research. But Siemens appears in almost no television history. The reason might be an article about television published in Discovery magazine in 1928.

The article was written by Alan Archibald Campbell Swinton, the person who described all-electronic scanned television in Nature in 1908 before Philo Farnsworth was two years old. It began with a short history, which included a mention of the television experiments of George R. Carey of Boston, possibly the first person to use the word camera to describe an electronic device. And it said Carey’s work was in 1875. If so, the 1876 Siemens lecture couldn’t possibly have influenced him.

The article was written by Alan Archibald Campbell Swinton, the person who described all-electronic scanned television in Nature in 1908 before Philo Farnsworth was two years old. It began with a short history, which included a mention of the television experiments of George R. Carey of Boston, possibly the first person to use the word camera to describe an electronic device. And it said Carey’s work was in 1875. If so, the 1876 Siemens lecture couldn’t possibly have influenced him.

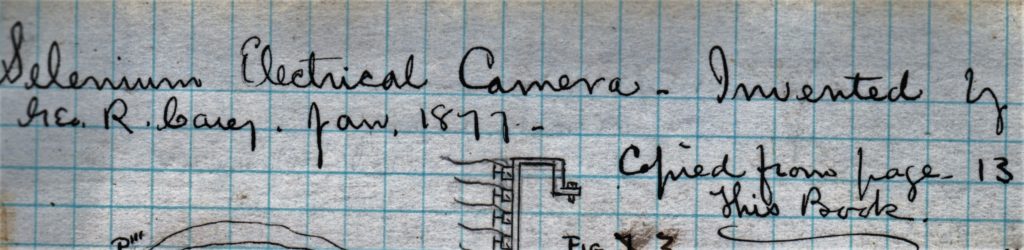

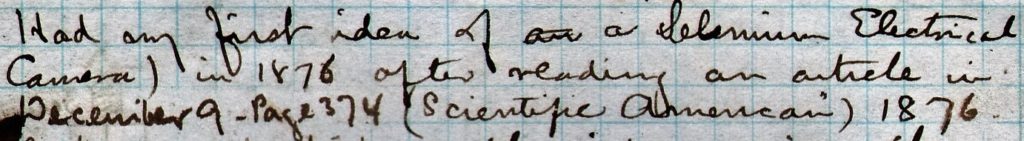

The 1875 date was erroneous and was debunked by the great television historian George Shiers in his paper “Historical Notes on Television Before 1900,” which appeared in the SMPTE Journal in March 1977. Perhaps it had been dictated, and a nine was misheard as a five; the earliest published information on Carey’s work was in 1879. But recently his unpublished, but witnessed, notebooks were acquired by The Karpeles Manuscript Library Museums. Through their courtesy, below are two images from Carey’s notebooks. The first is dated January 1877, which is the earliest known date for television research. The second mentions as the source of his inspiration an article on page 374 of the December 9, 1876 issue of Scientific American.

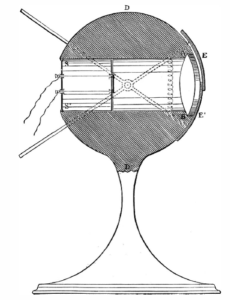

What was the subject of that article? It was something shown at the end of the Siemens lecture. “Before concluding,” he said, “I wish to introduce to your notice a little apparatus, which I have prepared to illustrate the extraordinary sensitiveness of my brother’s selenium preparations and an analogy between its action and that of the retina of our eye.” With that introduction, Siemens showed a device with a selenium “retina,” lens, and even “eyelids.” “Here we have then an artificial eye, which is sensible to light and to differences of color, which shows the phenomenon of fatigue if intense light is allowed to act for a length of time, and from which it recovers again by repose in keeping the eyelids closed.”

At best, it was a one-pixel camera, but the idea of even that in 1876 was so extraordinary that it was picked up by journals, newspapers, and magazines around the world, from The Great Bend Weekly Tribune in Kansas to the Bruce Herald in New Zealand. It might be the single most-famous invention you’d never heard of. And Carey wasn’t the only person inspired to begin television research based on that lecture. Adriano de Paiva in Portugal and Constantin Senlecq in France also mentioned the Siemens eye, as did still-picture-transmission researcher Carlo Perosino in Italy. Whether it was called an artificial eye, occhio selenico, œil artificiel, ojo artificial, or olho artificial, it appeared in reports of much of the early television research. Prior to 1877, there does not appear to be a single mention of anything that could be considered a video camera, not even in fantasy or fiction; in 1877, at least eight people, in multiple countries, on both sides of the Atlantic, began work on or mentioned something like it.

At best, it was a one-pixel camera, but the idea of even that in 1876 was so extraordinary that it was picked up by journals, newspapers, and magazines around the world, from The Great Bend Weekly Tribune in Kansas to the Bruce Herald in New Zealand. It might be the single most-famous invention you’d never heard of. And Carey wasn’t the only person inspired to begin television research based on that lecture. Adriano de Paiva in Portugal and Constantin Senlecq in France also mentioned the Siemens eye, as did still-picture-transmission researcher Carlo Perosino in Italy. Whether it was called an artificial eye, occhio selenico, œil artificiel, ojo artificial, or olho artificial, it appeared in reports of much of the early television research. Prior to 1877, there does not appear to be a single mention of anything that could be considered a video camera, not even in fantasy or fiction; in 1877, at least eight people, in multiple countries, on both sides of the Atlantic, began work on or mentioned something like it.

The Siemens artificial eye might not have been television’s start, but it certainly got the ball rolling.