B4 Long

Story Highlights

Something extraordinary happened at this month’s annual convention of the National Association of Broadcasters in Las Vegas. Actually, it was more a number of product introductions — from seven different manufacturers — adding up to something extraordinary: the continuation of the B4 lens mount into the next era of video production.

Something extraordinary happened at this month’s annual convention of the National Association of Broadcasters in Las Vegas. Actually, it was more a number of product introductions — from seven different manufacturers — adding up to something extraordinary: the continuation of the B4 lens mount into the next era of video production.

Perhaps it’s best to start at the beginning. The first person to publish an account of a working solid-state television camera knew a lot about lens mounts. His name was Denis Daniel Redmond, his account of “An Electric Telescope” was published in English Mechanic and World of Science on February 7, 1879, and the reason he knew about lens mounts was that, when he wasn’t devising new technologies, he was an ophthalmic surgeon.

It would be almost half a century longer before the first recognizable video image of a human face could be captured and displayed, an event that kicked off the so-called mechanical-television era, one in which some form of moving component scanned the image in both the camera and the display system. At left above, inventor John Logie Baird posed next to the apparatus he used. The dummy head (A) was scanned by a spiral of lenses in a rotating disk.

It would be almost half a century longer before the first recognizable video image of a human face could be captured and displayed, an event that kicked off the so-called mechanical-television era, one in which some form of moving component scanned the image in both the camera and the display system. At left above, inventor John Logie Baird posed next to the apparatus he used. The dummy head (A) was scanned by a spiral of lenses in a rotating disk.

A mechanical-television camera designed by SMPTE-founder Charles Francis Jenkins, shown at right, used a more-conventional single lens, but it, too, had a spinning scanning disk. There was so much mechanical technology that the lens mount didn’t need to be made pretty.

A mechanical-television camera designed by SMPTE-founder Charles Francis Jenkins, shown at right, used a more-conventional single lens, but it, too, had a spinning scanning disk. There was so much mechanical technology that the lens mount didn’t need to be made pretty.

The mechanical-television era lasted only about one decade, from the mid-1920s to the mid-1930s. It was followed by the era of cathode-ray-tube (CRT) based television: camera tubes and picture tubes. Those cameras also needed lenses.

The 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin might have been the first time that really long television lenses were used — long both in focal length and in physical length. They were so big (left) that the camera-lens combos were called Fernsehkanone, literally “television cannon.” The mount was whatever was able to support something that large and keep it connected to the camera.

The 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin might have been the first time that really long television lenses were used — long both in focal length and in physical length. They were so big (left) that the camera-lens combos were called Fernsehkanone, literally “television cannon.” The mount was whatever was able to support something that large and keep it connected to the camera.

In that particular case, the lens mount was bigger than the camera. With the advent of color television and its need to separate light into its component colors, cameras grew.

At right is an RCA TK-41 camera, sometimes described as being comparable in size and weight to a pregnant horse; its viewfinder, alone, weighed 45 lbs. At its front, a turret (controlled from the rear) carried a selection of lenses of different focal lengths, from wide angle to telephoto. Behind the lens, a beam splitter fed separate red, green, and blue images to three image-orthicon camera tubes.

At right is an RCA TK-41 camera, sometimes described as being comparable in size and weight to a pregnant horse; its viewfinder, alone, weighed 45 lbs. At its front, a turret (controlled from the rear) carried a selection of lenses of different focal lengths, from wide angle to telephoto. Behind the lens, a beam splitter fed separate red, green, and blue images to three image-orthicon camera tubes.

The idea of hand-holding a TK-41 was preposterous, even for a weight lifter. But camera tubes got smaller and, with them, cameras.

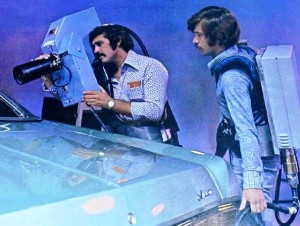

RCA’s TK-44, with smaller camera tubes, was adapted into a “carryable” camera by Toronto station CFTO, but it was so heavy that the backpack section was sometimes worn by a second person, as shown at the left. The next generation actually had an intentionally carryable version, the TKP-45, but, even with that smaller model, it was useful for a camera person to be a weightlifter, too.

RCA’s TK-44, with smaller camera tubes, was adapted into a “carryable” camera by Toronto station CFTO, but it was so heavy that the backpack section was sometimes worn by a second person, as shown at the left. The next generation actually had an intentionally carryable version, the TKP-45, but, even with that smaller model, it was useful for a camera person to be a weightlifter, too.

At about the same time as the two-person adapted RCA TK-44, Ikegami introduced the HL-33, a relatively small and lightweight color camera. The HL stood for “Handy-Looky.” It was soon followed by the truly shoulder-mountable HL-35, shown at right.

At about the same time as the two-person adapted RCA TK-44, Ikegami introduced the HL-33, a relatively small and lightweight color camera. The HL stood for “Handy-Looky.” It was soon followed by the truly shoulder-mountable HL-35, shown at right.

The HL-35 achieved its small form factor through the use of 2/3-inch camera tubes. The outside diameter of the tubes was, indeed, 2/3 of an inch, about 17 mm, but, due to the thickness of the tube’s glass and other factors, the size of the image was necessarily smaller, just 11 mm in diagonal.

Many 2/3-inch-tubed cameras followed the HL-35. As with cameras that used larger tubes, the lens mount wasn’t critical. Each tube could be moved slightly into the best position, and its scanning size and geometry could also be adjusted. Color-registration errors were common, but they could be dealt with by shooting a registration chart and making adjustments.

The CRT era was followed by the era of solid-state image sensors. They were glued onto color-separation prisms, so the ability to adjust individual tubes and scanning was lost. NHK, the Japan Broadcasting Corporation, organized discussions of a standardized lens-camera interface dealing with the physical mount, optical parameters, and electrical connections. Participants included Canon, Fuji, and Nikon on the lens side and Hitachi, Ikegami, JVC, Matsushita (Panasonic), Sony, and Toshiba on the camera side.

The CRT era was followed by the era of solid-state image sensors. They were glued onto color-separation prisms, so the ability to adjust individual tubes and scanning was lost. NHK, the Japan Broadcasting Corporation, organized discussions of a standardized lens-camera interface dealing with the physical mount, optical parameters, and electrical connections. Participants included Canon, Fuji, and Nikon on the lens side and Hitachi, Ikegami, JVC, Matsushita (Panasonic), Sony, and Toshiba on the camera side.

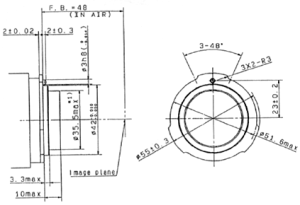

To allow the use of 2/3-inch-format lenses from the tube era, even though they weren’t designed for fixed-geometry sensors, the B4 mount (above left) was adopted. But there was more to the new mount than just the old mechanical connection. There were also specifications of different planes for the three color sensors, types of glass to be used in the color-separation prism and optical filters, and electrical signal connections for iris, focus, zoom, and more.

When HDTV began to replace standard definition, there was a trend toward larger image sensors, again — initially camera tubes. After all, more pixels should take up more space. Sony’s solid-state HDC-500 HD camera used one-inch-format image sensors instead of 2/3-inch. But existing 2/3-inch lenses couldn’t be used on the new camera. So, even though those existing lenses were standard-definition, the B4 mount continued, newly standardized in 1992 as Japan’s Broadcast Technology Association S-1005.

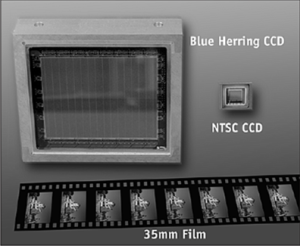

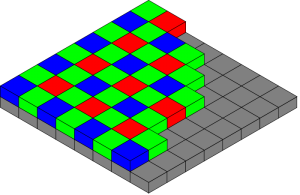

The first 4K camera also sized up — way up. Lockheed Martin built a 4K camera prototype using three solid-state sensors (called Blue Herring CCDs, shown at left), and the image area on each sensor was larger than that of a frame of IMAX film.

The first 4K camera also sized up — way up. Lockheed Martin built a 4K camera prototype using three solid-state sensors (called Blue Herring CCDs, shown at left), and the image area on each sensor was larger than that of a frame of IMAX film.

As described in a paper in the March 2001 SMPTE Journal, “High-Performance Electro-Optic Camera Prototype” by Stephen A. Stough and William A. Hill, that meant a large prism. And a large prism meant a return to a camera size not easily shouldered (shown above at right).

That was a prototype. The first cameras actually to be sold that were called 4K took a different approach, a single large-format (35 mm movie-film-sized) sensor covered with a patterned color filter.

That was a prototype. The first cameras actually to be sold that were called 4K took a different approach, a single large-format (35 mm movie-film-sized) sensor covered with a patterned color filter.

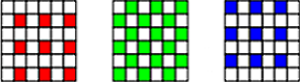

An 8×8 Bayer pattern is shown at right, as drawn by Colin M. L. Burnett. The single sensor and its size suggested a movie-camera lens mount, the ARRI-developed positive-lock or PL mount.

One issue associated with the color-patterned sensors is the differences in spatial resolution between the colors. As seen at left, the red and blue have half the linear spatial resolution of the sensor (and of the green). Using an optical low-pass filter to prevent red and blue aliases would eliminate the extra green resolution; conversely, a filter that works for green would allow red and blue aliases. And, whether it’s called de-Bayering, demosaicking, uprezzing, or upconversion, changing the resolution of the red and blue sites to that of the overall sensor requires some processing.

One issue associated with the color-patterned sensors is the differences in spatial resolution between the colors. As seen at left, the red and blue have half the linear spatial resolution of the sensor (and of the green). Using an optical low-pass filter to prevent red and blue aliases would eliminate the extra green resolution; conversely, a filter that works for green would allow red and blue aliases. And, whether it’s called de-Bayering, demosaicking, uprezzing, or upconversion, changing the resolution of the red and blue sites to that of the overall sensor requires some processing.

Another issue is related to the range of image-sensor sizes that use PL mounts. At right is a portion of a guide created by AbelCine showing shot sizes for the same focal-length lens used on different cameras <http://blog.abelcine.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/35mm_DigitalSensors_13.jpg>. In each case, the yellowish image is what would be captured on a 35-mm film frame, and the blueish image is what the particular camera captures from the same lens. The windmill at the left, prominent in the Canon 5D shot, is not in the Blackmagic Design Cinema Camera shot.

Another issue is related to the range of image-sensor sizes that use PL mounts. At right is a portion of a guide created by AbelCine showing shot sizes for the same focal-length lens used on different cameras <http://blog.abelcine.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/35mm_DigitalSensors_13.jpg>. In each case, the yellowish image is what would be captured on a 35-mm film frame, and the blueish image is what the particular camera captures from the same lens. The windmill at the left, prominent in the Canon 5D shot, is not in the Blackmagic Design Cinema Camera shot.

Whatever their issues, thanks to their elimination of a prism, the initial crop of PL-mount digital-cinematography cameras, despite their large-format image sensors, were relatively small, light, and easily carried. Their size and weight differences from the Lockheed Martin prototype were dramatic.

There was a broad selection of lenses available for them, too — but not the long-range zooms with B4-mount lenses needed for sports and other live-event production. It’s possible to adapt a B4 lens to a PL-mount camera, but an optically perfect adaptor would lose more than 2.5 stops (equivalent to needing about six times more light). Because nothing is perfect, the adaptor would introduce its own degradations to the images from lenses designed for HD, not 4K (or Ultra HD, UHD). And a large-format long-range zoom lens would be a difficult project. So multi-camera production remained largely B4-mount three-sensor prism-based HD, while single-camera production moved to PL-mount single-sensors with more photo-sensitive sites (commonly called “pixels”).

Then, at last year’s NAB Show, Grass Valley showed a B4-mount three-sensor prism-based camera labeled 4K. Last fall, Hitachi introduced a four-chip B4-mount UHD camera. And, at last week’s NAB Show, Ikegami, Panasonic, and Sony added their own B4-mount UHD cameras. And both Canon and Fujinon announced UHD B4-mount long-range zoom lenses.

The camera imaging philosophies differ. The Grass Valley LDX 86 is optically a three-sensor HD camera, so it uses processing to transform the HD to UHD, but so do color-filtered single-sensor cameras; it’s just different processing. The Grass Valley philosophy offers appropriate optical filtering; the single-sensor cameras offer resolution assistance from the green channel.

The camera imaging philosophies differ. The Grass Valley LDX 86 is optically a three-sensor HD camera, so it uses processing to transform the HD to UHD, but so do color-filtered single-sensor cameras; it’s just different processing. The Grass Valley philosophy offers appropriate optical filtering; the single-sensor cameras offer resolution assistance from the green channel.

Hitachi’s SK-UHD4000 effectively takes a three-sensor HD camera and, with the addition of another beam-splitting prism element, adds a second HD green chip, offset from the others by one-half pixel diagonally. The result is essentially the same as the color-separated signals from a Bayer-patterned single higher-resolution sensor, and the processing to create UHD is similar.

Hitachi’s SK-UHD4000 effectively takes a three-sensor HD camera and, with the addition of another beam-splitting prism element, adds a second HD green chip, offset from the others by one-half pixel diagonally. The result is essentially the same as the color-separated signals from a Bayer-patterned single higher-resolution sensor, and the processing to create UHD is similar.

Panasonic’s AK-UC3000 uses a single, color-patterned one-inch-format sensor. To use a 2/3-inch-format B4 lens, therefore, it needs an optical adaptor, but the adaptor is built into the camera, allowing the electrical connections that enable processing to reduce lens aberrations. Also, the optical conversion from 2/3-inch to one-inch is much less than that required to go to a Super 35-mm movie-frame size.

Panasonic’s AK-UC3000 uses a single, color-patterned one-inch-format sensor. To use a 2/3-inch-format B4 lens, therefore, it needs an optical adaptor, but the adaptor is built into the camera, allowing the electrical connections that enable processing to reduce lens aberrations. Also, the optical conversion from 2/3-inch to one-inch is much less than that required to go to a Super 35-mm movie-frame size.

Both Ikegami’s UHD camera (left) and Sony’s HDC-4300 (right) use three 2/3-inch-format image sensors on a prism block, but each image sensor is truly 4K, making them the first three-sensor 4K cameras since the Lockheed Martin prototype. By increasing the resolution without increasing the sensor size, however, they have to contend with photo-sensitive sites a quarter of the area of those on HD-resolution chips, reducing sensitivity.

Both Ikegami’s UHD camera (left) and Sony’s HDC-4300 (right) use three 2/3-inch-format image sensors on a prism block, but each image sensor is truly 4K, making them the first three-sensor 4K cameras since the Lockheed Martin prototype. By increasing the resolution without increasing the sensor size, however, they have to contend with photo-sensitive sites a quarter of the area of those on HD-resolution chips, reducing sensitivity.

It might seem strange that camera manufacturers are moving to B4-mount 2/3-inch-format 4K cameras at a time when there are no B4-mount 4K lenses, but the same thing happened with the introduction of HD. Almost any lens will pass almost any spatial resolution, but the “modulation transfer function” or MTF (the amount of contrast that gets through at different spatial resolutions) is usually better in lenses intended for higher-resolution applications, and the higher the MTF the sharper the pictures look.

With all five of the major manufacturers of studio/field cameras moving to 2/3-inch 4K cameras, lens manufacturers took note. Canon showed a prototype B4-mount long-range 4K zoom lens, and Fujinon actually introduced two models, the UA80x9 (left) and the UA22x8 (right). The lenses use new coatings that increase contrast and new optical designs that increase MTF dramatically even at HD resolutions.

With all five of the major manufacturers of studio/field cameras moving to 2/3-inch 4K cameras, lens manufacturers took note. Canon showed a prototype B4-mount long-range 4K zoom lens, and Fujinon actually introduced two models, the UA80x9 (left) and the UA22x8 (right). The lenses use new coatings that increase contrast and new optical designs that increase MTF dramatically even at HD resolutions.

There is no consensus yet on a shift to 4K production, but 4K B4-mount lenses on HD cameras should significantly improve even HD pictures. That’s nice!